Inflation Road Trip – Journey Through a Fragile Europe

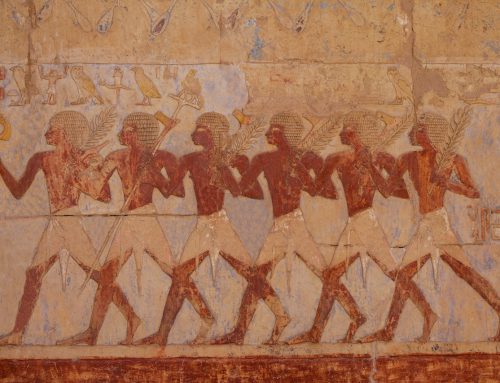

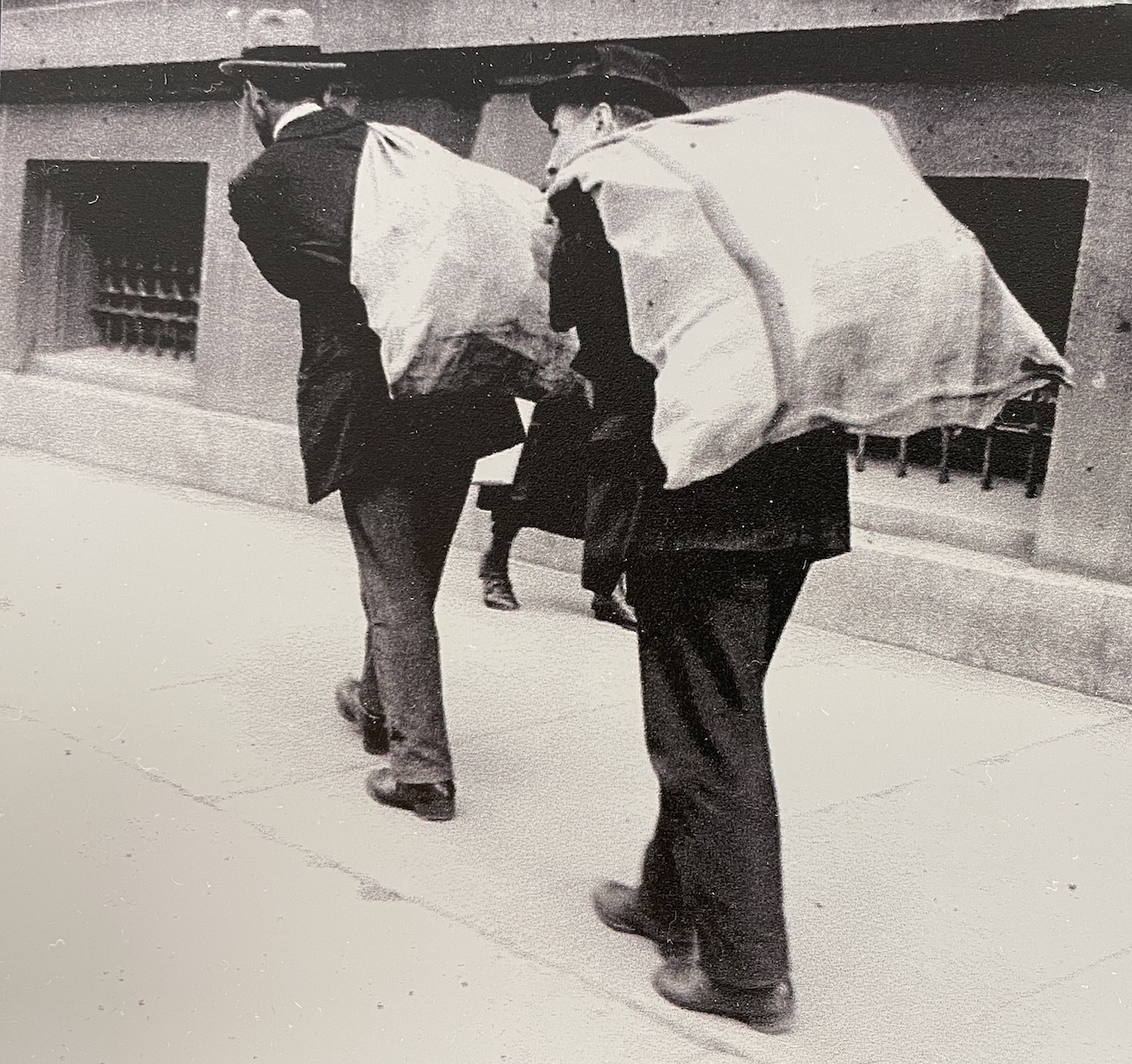

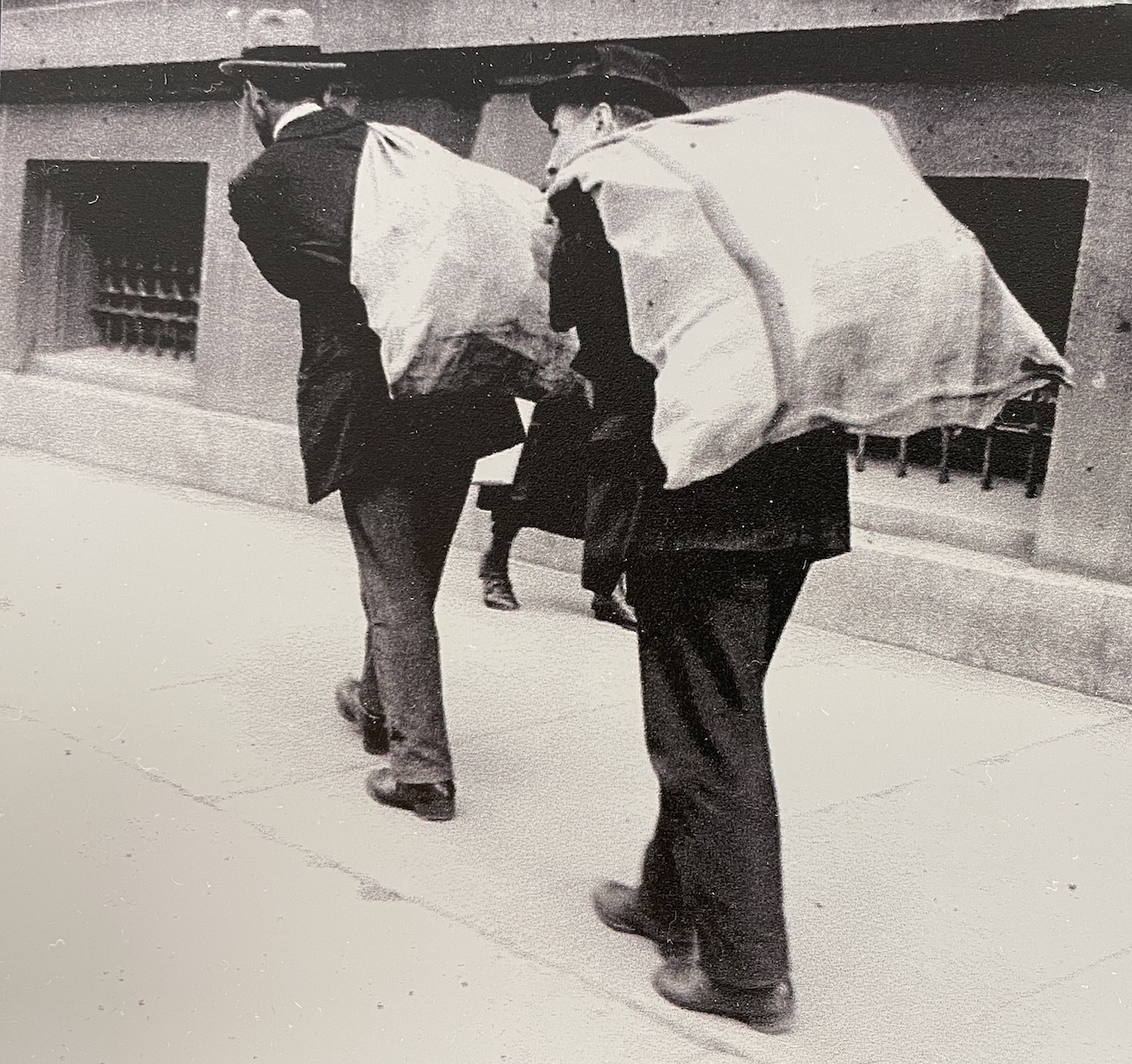

Sackfuls of money in 1923 Germany (courtesy Haus der Weimarer Republik)

Sackfuls of money in 1923 Germany (courtesy Haus der Weimarer Republik)

Inflation Road Trip

London - Prosperity and Fatigue

It began in darkness. London, 4:45 in the morning, drizzle on the windscreen and two empty beer bottles under the tree outside my flat. A man and a woman, both vagrants, passed by silently, heading somewhere with more purpose than comfort. Even before I had started the engine, I could sense the theme of my journey. Wealth on paper, weariness in reality.

This so-called Inflation Road Trip was never meant to be about travel for travel’s sake. For sure, I had to make it to Austria’s Krems, where I was scheduled to deliver a lecture, but it made sense to do something sensible on the way.

My journey was really about tracing the fault lines of today’s economy. The fragile confidence that underpins our currencies, our politics, and our sense of order. I wanted to see what inflation looks like, not in data or headlines, but in streets, cafés, and people’s eyes.

London remains prosperous, but it no longer feels confident. There are too many “To Let” signs, too many cafés half-full of laptop nomads, too many parking spaces in streets that used to heave with cars. The city functions, but half-heartedly. Politicians call this resilience. It feels more like fatigue.

When the time comes for global economics to falter, politicians are always the last to notice, certainly the last to react. They insist that everything is under control. It is what politicians said in 1923, 1929, 1973, and 2008. Each time, they were wrong. Each time, the public paid the price.

Liège - Decline and Economics

Crossing under the Channel and once I had emerged the far side, the motorway through northern France felt empty, almost too smooth. I then reached Belgium’s Liège, once a titan of European industry, but now a study in quiet decline.

There were closed shops with yellowed posters in the windows, graffiti reaching the rooftops, and men drinking canned beer in the city centre during the afternoon. It was not poverty in the Dickensian sense, but something subtler. Exhaustion perhaps, the kind that sets in when hope no longer pays interest.

A hotel receptionist told me the downturn began during the pandemic and deepened when a new tram divided the city centre. Businesses on the wrong side of the tracks simply died. Recovery never came. I thought of Britain, where lockdowns reshaped cities in similar ways. There were shifts in habit that quietly rewired economies.

The hotel car park was almost empty, and mine was the only British number plate. Once upon a time, that would have felt adventurous. Now it felt lonely. Globalisation, it seems, has a shrinking radius.

Liège taught me the first lesson of the road. You cannot measure economic health in statistics. You feel it in how people move, how they speak, how they look at the future. Liège, to my inexpert eye, did not look to be thriving.

Weimar – Lessons from History

Germany’s Weimar was next, perhaps five hours’ drive from Liège. When I reached it, I am unsure what I was expecting. Poverty and misery, perhaps. But no. Weimar was rain-washed and immaculate, a city of culture, intellect, and contradiction. Its cobbled streets and orderly façades disguised the fact that this was once the eye of a storm. It was the birthplace of the Weimar Republic, the democracy that, in 1919, tried to build itself on sand.

Four years later, in 1923, Germany’s money lost meaning. Hyperinflation destroyed savings, pensions, and trust. Essentially, everything that connected a citizen to the state. When value disappears, so does faith. There was trouble then, real trouble.

The museum at the Haus der Weimarer Republik explained clearly how the republic began with optimism in 1919, collapsed under hyperinflation in 1923, and was finally buried by the Wall Street crash of 1929. Out of that ruin came Hitler, who understood that desperation voted for certainty, not truth.

This week, as I was driving through Europe, gold prices fell steeply. I saw it as a culling, the market shaking off its fair-weather investors. I do not believe the official narrative that corporations and central banks were the main buyers. The dealers told me otherwise. Four-fifths of their customers were individuals, they advised. Real people, quietly hedging their futures. While gold wobbled, the stock markets climbed, an irony that would have made a Weimar banker smile. Markets often rise the longest when logic has already left the room.

Weimar to Krems - Europe’s Patchwork

The next morning, I left early, having joked with the breakfast waitress that my porridge should be made by a Scot in a kilt. For a moment, she took me seriously, then laughed. Humour still crosses borders, even when money does not.

The autobahns south towards Krems were lined with lorries from Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, even Kazakhstan. There were none from Britain. We have become spectators to a continent we once helped to build.

Rain turned the forests gold and red. They were strangely beautiful. Service stations smelled of diesel and resignation. At one, a worker told me the wet weather was unusual. It was bucketing with rain, my wipers going full speed and still not working properly.

“Not for me,” I said, adding, “I live in the UK’s Lake District, where rain is a way of life.” We both laughed, a small solidarity of shared discomfort.

Yet beneath the scenery, and the Armageddon-like rainstorm, I kept thinking of 1929, when America called in its loans and Germany crumbled. Today, the dependence on the US remains. Central banks hoard gold for the same reason - insurance against Washington’s mood swings. When the dollar sneezes, the rest of the world still catches cold. I sense the planet is trying hard to fashion an alternative. Dollar out, something else to appear. I doubt it will be long.

Along the route, solar panels carpeted the fields. Wind turbines rotated lazily above the hedgerows. An empire of optimism - clean, silent, and hungry for land. Progress always leaves a footprint, even when it is green. Once upon a time, these fields would have grown crops for mankind to gobble. Now they produce energy.

At the border between Germany and Austria, the lorries were diverted for inspection, while the cars were waved through. Nearby, a field of saplings encased in plastic tree tubes reminded me that good intentions still produce bad materials.

To the east, pylons marched beside the road, ending abruptly at the Czech frontier. Electricity, like politics, respects borders. It seems that members of the European Union do not always share. It is a union that appears disunited.

The Danube - Liquidity and Trust

The Danube, which the locals call the Donau, kept appearing, as it wound this way and that like some massive snake. It was swollen from days of rain. At Passau, three rivers meet - the Danube for sure, plus the Inn and Ilz. It was here, after the hyperinflation years, that trade revived the region. Water became wealth again. Money, just like rivers, depends on flow. When the flow stops, when credit seizes, when trust evaporates, the economy floods or dries. Stability lies in the balance.

I then passed Linz, its Ars Electronica Center glowing on the riverbank, a symbol of a Europe rebuilt by machines. Industrial scars had been repurposed as innovation. It was the late afternoon, and as the light began to fade, I wondered whether Europe had healed its soul as efficiently as it had healed its factories.

I then reached Krems, my objective. The Danube is there, too, and ran high but was just contained, its banks firm. It would not take much for flooding to occur, which was perhaps why I saw no boat traffic on the river at all. It would have been far too risky for boats, the river, and the population. Meanwhile, the town itself looked peaceful, again cobbled, and again charming. Perhaps, I thought, Krems was a place between floods.

Europe’s Past, the World’s Future

From London, to Liège, to Weimar, to Krems, and many places in between, Europe felt stable on the surface yet uneasy beneath. It was the same illusion that haunted the 1920s. Prosperity built on borrowed time. Perhaps the calm before the slide. Those were the so-called Roaring Twenties, a decade of significant economic prosperity, cultural dynamism and social change.

The UK, meanwhile, currently stands on its own island of contradictions. There is wealth concentrated, infrastructure crumbling, optimism rationed, and a deeply unpopular government. Some might call it resilience - not me - but resilience without reform is just stubbornness.

It is tempting to believe that because the world has been through Weimar’s 1923 catastrophe, followed by the stock market crash of 1929, it cannot be repeated. Not true. Knowledge and experience do not immunise, they merely explain. The same forces still exist. Debt, speculation, inequality, complacency. To say, “This time is different”, is self-deception. History has a sad habit of repeating itself.

The likely outcome? I have no idea, but a slow decline, rather than a sudden collapse seems more likely. Inflation erodes quietly. Democracies fade gradually. Empires collapse in stages. The end arrives not with a crash, but with a shrug.

The Human Economy - Trust Endures

For all that, the road was not bleak. There were moments of humour, kindness, and even absurdity. There were the human constants that outlast systems. I can remember at least three.

The barista in Liège who insisted I take an extra, complimentary biscuit “for the road.” The student in Weimar who spoke of democracy as if it were a craft, not a gift. And the service-station attendant in Bavaria who laughed about the rain. Each of them was worth more than any ounce of gold.

Looking Ahead - After Confidence

Economic breakdowns do not announce themselves. They accumulate. For now, the numbers look respectable, the markets rise, the politicians smile. Mind you, politicians are masterful at the positive spin.

Meanwhile, the stock markets before the 1929 crash were somewhere near the sky. The Dow Jones rose sixfold between 1921 and 1929. By 1932, it had lost almost 90% of its peak value and did not recover for 25 years.

After the crash, President Roosevelt outlawed the private ownership of gold and then devalued the dollar. This effectively raised the value of gold by 69%. It was 41 years later that the ownership of gold was again permitted.

Yet history is patient. It has to be. When confidence fades, and it always does, the cycle resets. Wealth moves quietly, fear moves faster, and most people are left wondering what happened.

Driving through Europe, I saw the signs. There were empty windows, silent factories, cheerful denial. The continent is not dying, but it is drifting. It is confident in form, cautious in spirit.

There are similar signs in the UK. I sense my country is at the vanguard of awfulness. Multiple houses are for sale, their prices are dropping, unemployment is rising, as is inflation. It appears that 30% of junior doctors are now unemployed, and plenty must still repay what they owe, job or no job. The average medical student debt in the UK is presently £70-90,000. That is massive. Meanwhile, many wealthy businesspeople have already left the land, hoping to avoid the mayhem caused by an unpredictable tax regime. I will not even mention immigration, which is essentially out of control.

The Danube in Krems, its current dark and strong, actually gave me an economic lesson. Neither rivers nor economies can be dammed forever. They must flow, and when they flood, it is frequently the low-lying who suffer. The high flyers have already departed.

Conclusion - Lessons from the Road

With my arrival in Krems, my Inflation Road Trip had ended, but the story it told was still unfolding. We are living, again, in an age of expensive optimism and cheap truth, just like the Roaring Twenties.

If Weimar, Liège, and London have taught me anything, it is that economies do not collapse when numbers fail. They collapse when belief goes out the window. I sense it is leaving already.

Until the next time, keep travelling, keep watching, try to make sense of the numbers for what they are worth, and above all else, keep smiling. Smiling, after all, is free.

***

#InflationRoadTrip #NeverAStraightLine #EconomicHistory #GlobalEconomy #WeimarLessons #EuropeInCrisis #FinancialConfidence #TravelAndObservation #TrustAndValue #ModernWeimar

Empty beer bottles in central London

Closed shops in Liège

Where the Weimar Republic was created in 1919

Weimar - one of many cobbled (and classy) streets

Autumn colours near the Danube in Krems

Downtown Krems

River Danube at Krems