We’ve run out of strychnine

Alnwick Poison Garden - enter with caution (courtesy Alnwick Gardens)

Alnwick Poison Garden - enter with caution (courtesy Alnwick Gardens)

Alnwick, United Kingdom

“It’s been a bad year,” said the guide. “We’ve only enough ricin to kill 18,000 people. Normally it would be more. And strychnine? We cannot obtain the seed.”

It was a drizzly day in the Alnwick Poison Garden, said to house the world’s most dangerous plants. The guide was fully in his stride.

“Shame about the strychnine,” I noted facetiously. The guide nodded and wandered on.

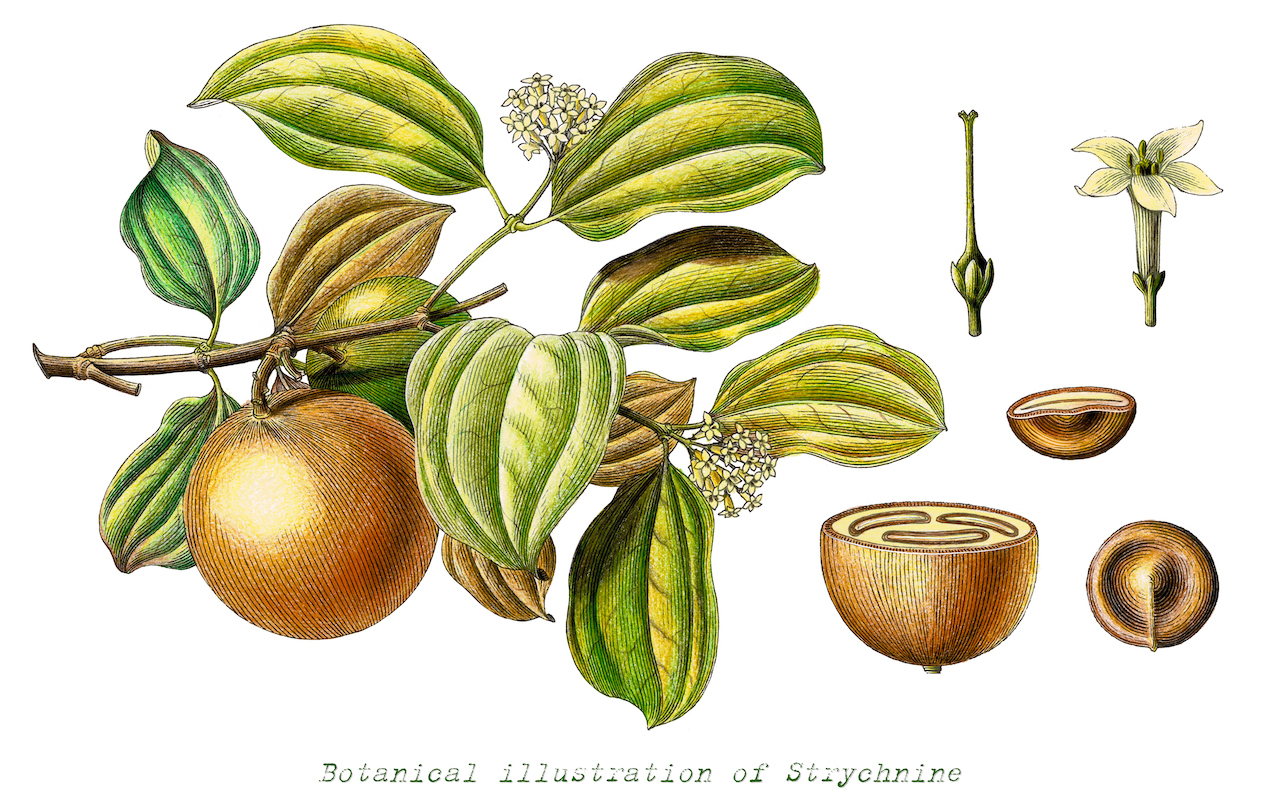

Strychnine is the product of the Strychnos nux-vomica plant, which is boring in appearance, but a favoured poison of Agatha Christie. A glug of strychnine and, 20 minutes later, muscle spasms begin. Two hours after that you are dead. Alexander the Great was said to have perished that way, with strychnine added to his wine in 323 BC. Plenty of others have been poisoned since, strychnine remaining a popular weapon for anyone wishing to do away with an enemy. Despite its detrimental effect, strychnine can have benefits. It is an antioxidant, relieves pain, helps diabetes, and may even ameliorate influenza, constipation, and back pain. My secret was nearly out as my back was killing me. I had hoped to have an illicit munch of Strychnos nux-vomicawhen no one was looking but such was not to be. No strychnine in the garden meant my back pain was there to stay.

“You’ll remember ricin,” the guide continued, standing beside another flower bed a few steps away. “Georgi Markov?”

I nodded. The Bulgarian journalist had been assassinated in 1978 by a ricin pellet shot from an umbrella on London’s Waterloo Bridge. Another Bulgarian defector had survived a similar attack, albeit in Paris, ten days earlier.

The guide pointed towards a castor oil plant growing innocently nearby. “Although a single bean contains only 4% ricin, the rest being castor oil, it can still kill 120 people,” he declared.

The Poison Garden was the brainchild of the Duchess of Northumberland, who inhabits nearby Alnwick Castle. A half-acre portion of the 14-acre Alnwick Gardens was fenced off in 2005, black gates added, adorned with two skulls and crossbones, and tours began. The initial aim was for drug education, with a short, 20-minute tour. Yet now more than 1000 people can visit daily, including police, chemical warfare specialists, school groups, and me.

“We ensure that everything here is harmful,” said the guide in a tone that would have driven Health & Safety crazy. “Even the box hedging.”

Bordering each bed of the Poison Garden was a low box hedge. Until then, I thought box was harmless. I was wrong. It can cause nausea, vomiting, convulsions, even respiratory failure. What the Poison Garden demonstrated so perfectly, and what my guide explained, was that normal gardening is more dangerous than you think. Much of what I have taken for granted can be harmful. Cherry laurel? The leaves are laden with cyanide, so never burn laurel when you have cut it, nor leave it in your car overnight.

Common rue? Phototoxicity - you can be blistered in moments. Medlars? Eat ten fruits from what the Indians call the suicide tree, and you will not last long.

The Alnwick Poison Garden may be small but is large on education. My expertly guided wander around its beds turned my limited gardener’s knowledge inside out. Hellebores, fritillaria, hogweed, rosemary, bay, laburnum, meadowsweet, and white willow can each be a problem. My garden contains many of them. The Poison Garden even grew khat and cannabis. The first may be a stimulant favoured by Somali pirates although it eventually rots their tongues. Meanwhile the garden harboured male, female, and hermaphrodite forms of cannabis. Sexing a cannabis plant is important, as only the female produces buds.

Leaving the Poison Garden required me to walk through a tunnel of Irish ivy. Feeling spooked would be an understatement. “Am I OK in here?” I asked my guide. He was at ease, hands in pockets, and talking for our country.

“No worries,” he replied. “You don’t want to touch the Irish ivy, as it may cause blistering. Its dust can certainly trigger asthma.”

“Shall I hold my breath?” I queried.

“Lots of people do,” the guide replied, “but there is no need. A few have collapsed but not many.”

I was not reassured.

I hurried through the ivy tunnel, hands in my pockets as well, and secretly held my breath. I was soon through and out, back to Alnwick fresh air and thanked the guide for my survival. He was busy, waved to me casually, and turned to greet a group of visitors, who were lined up patiently beside the Poison Garden’s black entrance gates.

The Poison Garden had taught me plenty, and in a very short time. I will never look at any garden in the same way again.

Strychnos nux-vomica, the source of strychnine, although Alnwick could not obtain the seed (courtesy channarongsds)

Ricinus communis – from which comes castor oil and ricin (courtesy Margaret Whittaker)

A medlar (Mespilus germanica) - eat ten of these and you are history

Cannabis sativa – this can have a very therapeutic effect (Photo by Matthew Brodeur on Unsplash)

The Grand Cascade of Alnwick Gardens – a truly beautiful place (courtesy Alnwick Gardens)