Skeleton 61 – osteoarchaeology with Andante

Winchester - once a major Roman garrison (courtesy Sterling750)

Winchester - once a major Roman garrison (courtesy Sterling750)

Winchester, United Kingdom

“Why are you here?” I asked the woman. We were attending the same course and it seemed polite to make conversation.

“Ritual killings,” she said. There was nothing I could usefully reply.

It was Winchester and once again I was a student. This time it was a world called osteoarchaeology, which is the study of ancient bones. Winchester is a good place for this, as the city, which was built in 70AD, was a Roman stronghold known as Venta Belgarum. The last Roman soldier left Britain in 407AD, but the result of this occupation was many hundreds of graves. It is why Andante Travels holds a day-long course there on human osteoarchaeology. The principle of the specialty is simple. Find a skeleton in a cemetery, retrieve what bones are intact, and see what can be concluded about their owner.

So it was that I sat in a Winchester church hall with 12 others, listening to an osteoarchaeologist who specialised in human decapitation, telling us what bones can reveal. I was prepared to be upset, disgusted and bored. After all, I have never been taught by a decapitation expert before. I ended up fascinated and enthralled, as the bones of the dead say plenty about the living.

My fellow students were reluctant to declare why they had come, other than the lady engrossed by ritual killings. Yet it was clear they all were former professionals. Many were medical, I could tell from the way they spoke, and each appeared to be of pensionable age. Of the dozen attendees, nine were women, a gender split I could not explain. What is it about ladies and bones?

The lecture hall was vast, and the instructor flashed images of mutilation and agony past us on a screen. Yet despite the gore it was interesting. I learned that men have sloping foreheads, but women do not, that an adult has 206 bones while a tiny baby has 270, and if you carry heavy loads, you develop dents in your vertebrae. I heard plenty more as well.

Andante looked after our tummies and ensured they were continually full. Not that the gory images made me especially hungry. The lunchtime grub was nothing flash and somehow my Coronation Chicken sandwich ended up on my lap. Thirty minutes later, when the lectures restarted, I looked to have been on an outdoor survival course. No one seemed to notice.

Three hours into the day, and despite my disaster with the sandwich, I felt trained in the theoretical oddities of Roman bones. It was time for the real thing. I was led to a table surfaced with bubble-wrap and joined three lady colleagues to make our team of four. Our task was to analyse an assortment of bones, squashed into several plastic bags. This was Skeleton 61.

“I think she was high maintenance,” said one of the ladies, as together we studied the skull.

“Why do you say that?” I asked.

“She has perfect teeth,” came the reply.

Which was true. Beside us were two other teams studying different skeletons, each of which had rotten choppers. Our Skeleton 61 was in another league, and I immediately felt proud.

“How do we know she was a woman?” I queried.

“The length of her bones and the shape of her pelvis,” said another of my companions. “We have measured her thigh and shin bones. They show her to be roughly five-feet-two while her pelvis supports her being female.”

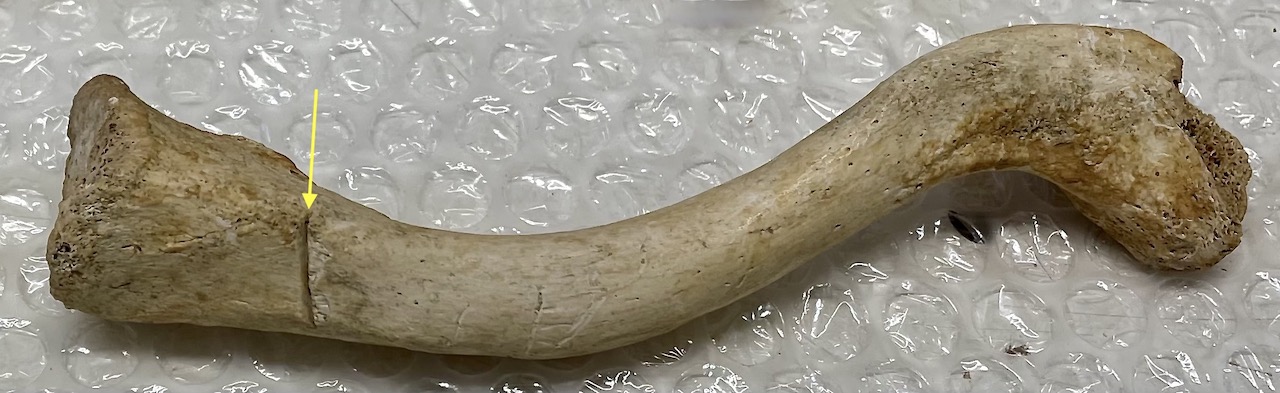

Our slow detective work continued, and as we delved further into Skeleton 61, we realised all was not the perfection we had first seen. Her teeth may have been good, but at one point she had broken her right elbow and nose, had a small lump on her head, a dodgy right hip, and had been plagued by sinusitis. She had been aged somewhere in her twenties.

Around us our fellow attendees filled the air with exclamations.

“Heavens!” said one, pointing to the sword mark on a collar bone, where the executioner had missed at a beheading.

“Look at this!” said another, holding high an ancient shin bone that showed evidence of a long-term infection.

“Glory be!” declared a third, pointing to a complicated break of a thighbone.

We were learning plenty. No longer were these bags of bones, they were real people.

“It is why we must treat them with respect,” said the instructor, who had joined us for our conclusions. “Some people give these skeletons names - Ruth, Mary, Doris. We don’t encourage naming. These were people like you and me.”

With that it was over, and I was on my way through the dense Winchester traffic. My day with dead people? Strangely it was interesting. I cannot claim to be an osteoarchaeologist but have taken the first step.

And so it began...osteoarchaeology underway in Winchester

Skeleton 61 - bones do tell a story

Skeleton 61 broke her elbow as a child (see arrow)

This one had his head chopped off, although someone missed and hit his collar bone (see arrow)