Drams mount up

The Lakes Distillery

The Lakes Distillery

Setmurthy, Cumbria, United Kingdom

I am uncertain why I visited The Lakes Distillery, but I am glad that I did. It is one of those places that has a presence. I should add that I am no drinker, perhaps a cider from time to time. Whisky is alien to me. At least it was until my tour of the distillery.

Somewhere near the northern tip of Britain’s Lake District, the country’s largest national park, and also a UNESCO World Heritage Site, a man called Paul Currie had a vision. He had made whisky in Scotland, on its scenic Isle of Arran, so why not do the same in England?

In 2014, close to charming Bassenthwaite Lake, and even closer to the River Derwent, he bought a group of rundown farmhouses. Two years later, and £5 million poorer, he had built The Lakes Distillery. The distillery now produces 400,000 bottles of whisky each year, as well as vodka and gin. There are tours, a bistro, a shop, lots of smiling staff, and somehow it is surviving a pandemic. Social distancing at The Lakes Distillery is now an artform.

The trouble with whisky is that you can believe anything of it. It is not just a drink distilled from fermented grain such as barley, corn, rye and wheat, but it comes with a history. Distillation as a process was practised by the Babylonians in 2000BC, followed by the Greeks in the first century AD, and the Arabs eight centuries later. By the 13th century monks were using whisky medicinally for colic and smallpox, doubtless other diseases, too. It is why we should drink it now.

In an era of Covid-19, when the leader of Belarus has recommended vodka as a pandemic cure, perhaps the English should turn to whisky. The spirit has been shown to promote weight loss, reduce stress, control diabetes, lower the risk of dementia, diminish blood clotting and boost immunity. The dentists have even tried sterilising toothbrushes with it, although sadly without effect. Whisky, and its wider properties, are so often ignored when perhaps we should pay them attention. After all the Gaelic description of whisky is uisge beathe. It means ‘water of life’. What more does one want in a pandemic?

Sadly, it is not all good news. The drink must be handled sensibly. The first Englishman to experience Covid-19, Connor Reed, once said that when he was a teacher in China’s Wuhan, which was where he acquired the disease, hot whisky controlled his cough. More than a thousand Iranians picked up the idea, thanks to social media, immediately overdosed on the alcohol they could find, and some died as a result. Casual comment ended in disaster.

Scotland, with its at least 97 distilleries, is seen by many to be the home of the drink, when in truth India is fastest growing for global whisky production. England has only 24 distilleries and is trying hard to catch up, as large and small establishments sprout in cities and countryside. The Lakes Distillery is in the vanguard of this drive and is setting standards that some can only dream to follow.

Whisky would not be whisky without a spooky story. It is one of the reasons for drinking. As the spirit takes over, as warmth flows from tongue to toe, the stories become more fantastical. The Glenrothes distillery ghost, the white stag of Arran, the Highlander and the Devil, and the story I love best - the origin of being late for one’s own funeral.

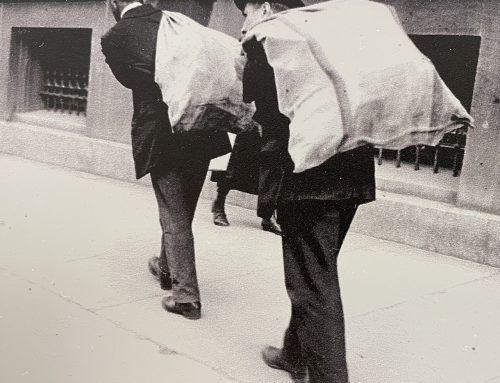

In the days when the dead were carried by men along coffin routes between villages - there is one between the Lake District’s Ambleside and Grasmere - it was customary for the bearers to stop at hostelries on the way. The coffin would be placed on specially made stones while the men took a dram of whisky at the inn. A dram was not big, despite popular thought. A true dram is barely 3.7 millilitres, less than a modern teaspoon. Yet drams mount up.

Once, it is said, a coffin party stopped at three inns on the way to the church, gathering up funeral attendees as they travelled. By the time the tiny, four-man party of bearers had swelled to more than one hundred, and dram had followed dram, few of the imminent congregation were sober. When they reached the church, they could have been anywhere.

“You’ve forgotten something,” said the gravedigger when the inebriated funeral party appeared.

“Forgotten what?” said the lead bearer, looking confused.

“The coffin,” came the reply.

Whisky had asserted its effect, the service was late starting while the forgotten coffin was collected, and thereafter came the saying that it was possible to be late for one’s own funeral.

The Lakes Distillery comes with its own sense of mystery, too. Penetrating its buildings’ walls, from outside to in, are 26 so-called quatrefoils, scattered over a wide area. Once called a caterfoil, the quatrefoil is a decorative design, thought to be of Islamic origin, that comprises four overlapping circles. Each part-circle has a meaning - faith, hope, love and luck. The distillery’s Quatrefoil Collection is based on these. Faith and Hope have appeared, Love is for the future, and Luck has just been released.

What better choice, in the middle of a pandemic, to have a drink that benefits health, and which the distillery has named Luck. Now where did I leave that bottle?

Bassenthwaite Lake and near the distillery (Mike Andrew)

Luck whisky, from the Quatrefoil Collection, was released in October 2020 (Lakes Distillery)

A Lake District coffin route

The quatrefoil, signifying faith, hope, love and luck (Lakes Distillery)