Wrinkles not an option

The Bader Hassoun Ecovillage and Soap Factory next door

The Bader Hassoun Ecovillage and Soap Factory next door

Tripoli, Lebanon

When I next see a piece of soap lying lonely in a dish, I swear I will spend a moment in reflection. After all, soap was always something simple, nothing special, and designed solely to help me wash. When out for my weekly shop, wandering aimlessly past regimented supermarket shelves, I would head straight for the shower gels in their fancy plastic containers. For a gift I would buy something classier. But the key was always simplicity and convenience. Soap was nothing remarkable. It was there merely to keep me clean.

It was then that I met Bader Hassoun in a place called Daher Al Ain.

Somewhere near the boundary of Tripoli, Lebanon’s northern city, lies an island of something exceptional, 30,000 square meters of magic. Green countryside, scattered rock, flat-topped trees sky-lining the horizon, a gorge-like river valley, birds singing, dogs dozing, kittens playing, traffic non-existent, and perfectly constructed stone buildings that looked to be from a film set.

The moment I passed through the high wrought-iron gates leading to this luxurious estate and found my footing on its well-laid cobbled surface, I realised I was somewhere remarkable. Bader Hassoun, the man who turned soap into an artform, appeared from a hidden doorway and within moments had begun to explain.

“I dreamed, I read, I studied,” he said. “I realised that different soaps could do different things. Soap is more than about washing.” As he spoke, he spread his arms widely, to show all he had created around him. Ten years earlier, where we stood, there had been nothing but open countryside.

“And the Ecovillage, the spa and the bungalows where people can stay,” he continued. “They will soon be finished.”

“What next?” I asked.

“There will always be something,” he replied. Was that a schoolboy grin? Bader Hassoun was a man with ideas, imagination and energy, features that his 200 daily visitors would testify.

But even to the soap novice, and that I fear was me, it was impossible to escape the diversity of soaps and oils around us in the tall display building as we spoke. Shelves, and carefully placed barrows, burgeoned with selections and designs. Different shapes of soap - round, square, rectangular, starred, pestle and mortar, and most definitely spherical. A sphere was the most traditional and somehow strangely attractive. It was how the Middle East made soap many hundreds of years ago. The colors - red, blue, green, orange, violet, brown, black, so many - were natural. Bader Hassoun was organic on legs.

A Man in Black, besuited, stood silently beside us. He listened carefully as Bader Hassoun spoke, and then gently took my right arm in his black-gloved right hand. Deftly, he placed a smidgeon of clear liquid on the bare skin of my forearm, stood back, and instructed, “Rub it in. Then smell.”

I did as requested, sniffing gently for fear I might not like it. Yet I need not have worried. The aroma was exquisite, warm, perhaps sweet, even slightly balsamic.

“That is oudh,” said the Man in Black. “It is one of the most expensive aromas in the world. They call it liquid gold. It brightens body and mind.”

Oudh - even I had heard of it. The wood from a South-East Asian agar tree, which when infected by a form of mold, reacts by creating a scented resin. Only 2% of agar trees produce it. No wonder oudh was so expensive.

I waited for the smidgeon to take effect, wondering how a brighter mind might feel. For a moment I sensed something flow through me, a flash perhaps, a sparkle, but then the Man in Black moved me onwards along the line of shelves, to the next and the next and the next. This, Bader Hassoun’s Soap Factory, was laden with aromas and suggestions.

Producing, and buying, aromas is not a saver’s activity. Fifty thousand US dollars for the Royal Collection, or US$2840 for the world’s most expensive bar of soap. I saw them both but touched neither. Yet there was plenty for those on a budget. Ten dollars? Twenty? Maybe slightly more. I did not need to be a zillionaire to visit the place, which I decided was just as well.

The aromas were many. Chamomile and tea, should you be romantic or if you wish to encourage a neonate to slumber. Lavender if stressed, mandarin for skin softening, mint to relieve cramps, musk for desire, rose for poor memory, and cedar wood, the most popular, which appeared good for just about anything.

“Does it work?” I asked, when I was shown a special soap that was designed to be anti-ageing. I never did establish the aroma.

“Of course,” came the reply from the Man in Black, who had now been joined by a besuited colleague. One travelling Englishman, two Men in Black, and Bader Hassoun looking on carefully. The Men in Black studied the ever-deepening wrinkles on my forehead with the concentration of uniformed soldiers defusing a landmine. They poked and prodded my face, played with the floppy skin beneath my eyes, flicked my ear lobes disapprovingly, and assessed the tone of sagging muscle around my mouth. I am the definition of disgraceful ageing, look like a species nearing extinction, but until that moment considered wrinkles to be a sign of wisdom. No chance. Wrinkles were not an option at the Soap Factory.

I must have looked doubtful, as the Men in Black hastened to continue. “We will show you,” said the first.

“Please sit there,” said the second, pointing at a trough-sized stone basin nearby. Beside it stood a neatly positioned woven-raffia and wooden chair. Obediently, I took my place.

“Lean back, close your eyes, and we will transform you,” said the Men in Black, who were speaking in almost unison.

“I have a suggestion,” I said, before doing as they instructed. Both Men in Black looked intrigued and waited for me to explain. The taller raised his eyebrows, indicating that I should speak.

“Just do the right side of my forehead,” I said. “Leave the left alone. That way, we can truly see if you transform me.” Then I leaned back, as they had requested.

On some hidden signal, the two set to work, keeping to the right side of my face and forehead. There was lathering of soap, splashing, massaging of my nose and eyelids, and deep discussion about crevasse-like wrinkles and the darkening blue bags beneath my eyes that were trying hard to reach the floor. Normally confident, as I sat on my chair beside the stone basin, I found it difficult not to feel self-conscious.

It finished as quickly as it started. Face done, although I had dared not look in a mirror, there followed the Thai massage. I was directed to another woven-raffia and wooden chair, my shirt was unbuttoned, and a Man in Black kneaded my knotted spine, manipulated my head to places it had not visited for a decade, and pulled at each of my fingers until they responded with a click. Somehow my hands remained intact.

Face done, massage done, I looked into the mirror I had avoided. For a moment I wondered what was looking back. I looked closer, then peered, the scientist on the verge of discovery.

“You’ve done it,” I declared, poking my cheekbones and forehead with a straight forefinger. “Where have they gone?”

The two men inspected me, peered left, studied right, and prodded my expression gently. Then both stood back. Each looked tired but I sensed were proud. Rejuvenating ageing Englishman was not simple. In a far corner I saw Bader Hassoun looking on, pretending to see nothing while witnessing everything, and then I saw him nod. The mirror told the tale. The right side of my forehead had become smooth and glossy, wrinkle-free, almost baby-like. On the left, my wrinkles persisted.

Bader Hassoun and his team of talented helpers had achieved something I had thought impossible. I looked younger, by an easy decade, at least my right side did, while the oudh rubbed into my forearm was already taking hold. I was relaxed, brighter, yet somehow everything seemed natural.

As I rose from the chair and headed from the building, my system reinvigorated, as I shook Bader Hassoun’s hand and thanked him for the experience, one question remained unanswered. How long would it last? Not the Soap Factory, as that seemed destined for expansion, but me. The wrinkle-free face, the spine that had not moved for ages, the spring to my step, and the oudh-induced feeling of enthusiasm.

Would it all scrub away when I took my first shower? I would only know once I had tried it. And never again would I look at soap lying lonely in its dish, because should you be Bader Hassoun, soap is a life experience.

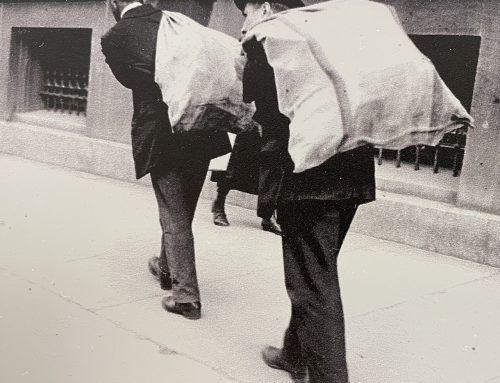

Bader Hassoun starts shaping a rectangular block of soap

The Man in Black sets to work on my forehead

Job done - wrinkles on the right have disappeared - oh, that such changes were permanent

Shapes and colours everywhere. So lifelike you can almost eat them.

The most expensive soap in the world - fancy paying US$2840