Recreating Cumberland

A warrior's path - the route from the battle on the way to Grisedale Tarn

A warrior's path - the route from the battle on the way to Grisedale Tarn

Dunmail Raise, Cumbria, United Kingdom

Walking in the footsteps of history can make me behave oddly. I realised that, as I scrambled up the bouldered path leading to the Lake District’s Grisedale Tarn from the busy main road below. The path had so much history, it was impossible to avoid being drawn in. I was following the same route, passing the same waterfalls, listening to the same crunching beneath my feet, as did King Dunmail’s warriors, more than a thousand years before me.

The year was 945AD and King Dunmail was ruler of Cumberland. Attacked by the combined forces of England’s King Edmund and Scotland’s King Malcolm, he retreated to a spot just north of Grasmere, and there fought his final battle. Legend has it that he was personally killed by Edmund, who also blinded both King Dunmail’s sons - fire branding was the favoured method - while captured Cumberland warriors were ordered to bury their master under a huge pile of stones. That pile is Dunmail Raise, a sad-looking mound that exists to this day and is now bounded on both sides by a dual carriageway that is a clear disrespector of history. Cars flash by at breakneck speed and I wager few drivers realise that a bare few yards from them lie the bones of the last King of Cumberland, buried in the very centre of the Raise. Or, so history would have it.

On that fateful day when Cumberland fell, there was a moment of something different, not solely the brutality of hand-to-hand combat. Determined not to lose everything, a loyal party of Cumberland survivors took the royal crown, it is said at their master’s instruction, and before he was killed in battle, when he commanded, “My crown! Bear it away! Never let the Saxon flaunt it!”

His followers climbed sure-footed into the mountains, fighting as they went, to seek out Grisedale Tarn, 538 metres above the sea. There was dense cloud, which helped them. The tarn - Northern English for a small lake - has only 11 hectares of surface, 33 metres of depth and is surrounded by three mountains, Fairfield, Seat Sandal and Dollywagon Pike. It was into the tarn the warriors flung the crown to keep it from enemy clutches, shouting as they threw, “’till Dunmail comes again to lead us!”

Each year on the battle’s anniversary, as legend has it, the warriors return to recover the crown, holding it aloft as they march over Seat Sandal, pick their way down the mountain’s stumbly surface, to once again reach the Raise. There they stop, knock the topmost stone with a spear, perhaps they knock again, and again, waiting for an answer. And then it comes, a voice from the inner depths of their master’s burial place, “Not yet, not yet. Wait a while, my warriors.”

Disappointed perhaps, the soldiers then make their way back, along the side of Raise Beck, and return to Grisedale Tarn. They throw the crown into the water once more, and one year later try again. Year follows year, and on each occasion they are instructed to wait. Yet all who live locally realise that, one day, the answer echoing from within that pile of stones will be different. The crown of Dunmail is charmed and its wearer has, by right, succession to the Kingdom of Cumberland. Cumberland may now have been dismantled and form part of modern Cumbria but be sure that is a minor issue if your name is Dunmail. He waits inside his Raise, biding time, until he can be sure he will be successful.

From legend comes ambition, particularly if you are a walker. What better way to spend a day as a modern Cumbrian hiker than to repeat that walk of history? The dash from valley into mountain, the steady climb alongside Raise Beck to reach Grisedale Tarn as it lies almost hidden, yet surrounded by mighty mountains. Then join the warriors as they return over Seat Sandal, to make their way back down to Dunmail Raise.

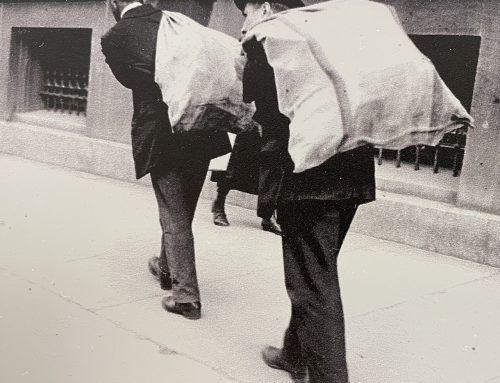

So I did it, and became a warrior for a day. Granted, I had no crown, just a floppy sunhat that had problems staying in position. Granted I had no sandals, but firm walking boots to protect me, and granted I carried a rucksack filled with modern items, objects that had not even been considered a thousand years ago. I had a full stomach, theirs would have been empty. I felt relaxed from a good night’s sleep, had two walking poles to avoid unexpected stumbles. They had been in a hurry, I was not, and no one was chasing me with a weapon.

Yet in my mind I was a warrior, fleeing from the enemy, set on preserving a treasure for my kingdom. Within me was a deep sense of history. I was on the same route as those survivors, the same place where Cumberland lost its king, the spot where so many had died. I may not have been escaping for my life, but certainly felt I was fleeing.

I slipped and slithered past the waterfalls of Raise Beck as they tumbled over greasy rocks. Water was coming down; I was going upwards. My carbide-tipped poles clickety-clicked, my boots squelched through mud patches and my hands, when poles permitted, grasped an occasional boulder for security. One proud stone, out of sight of both valley and road beneath me, and almost guarding some unexpected corner, was especially prominent. The size of two men, it was vertical and rectangular. It had most likely been there for a full geological era and was going nowhere in a hurry. For some reason I spoke to it. Yes, spoke to a stone.

“You’ve been here for a long time,” I said. The stone did not reply.

I reached out to grasp it with one hand, to ease myself around the corner. I was so immersed in fantasy, I could feel a crown in my hand, heard chasing voices behind, and despite the clear sky around me, imagined I was surrounded by cloud. As I touched the stone, I had the vision of other hands there before me. One had been escaping from battle and in my dreamy state, I saw bloodied knuckles.

Grisedale Tarn is dominant and scenic, and yet still appears well hidden. It is exactly the place I would choose if I wished to hide a crown. The tarn did not appear until I actually reached it. It is not a Windermere or a Coniston that can be seen from miles away. Grisedale Tarn was slightly sunken, with several false, tiny crests before I got there. Yet when I saw it, it was a place of beauty, of peace, somewhere to think and ponder. For a while I sat on a boulder, near one end of its expanse, and reflected on that day more than a thousand years earlier. The warriors would have been in a hurry, they would have been fleeing for their existence, perhaps even wounded, and taking advantage of the low cloud. Likely in haste they would have thrown the crown far into the water. It would have landed with a gentle splash; a fighter’s crown was more a circlet and not heavy. It would have slowly oscillated to the bottom.

There it lies to this day, still hidden to modern divers, who have repeatedly tried to find it but without success. Yet the crown is somehow retrieved each year by ghostly warriors, who then march over Seat Sandal to their master. They are certain, as am I, that Dunmail will return one day and Cumberland will be recreated.

Dunmail Raise - under this pile of stones lie the bones of King Dunmail

Grisedale Tarn - the hiding place of Cumberland's royal crown