Cumbrians love bad weather

The Fairfield Horseshoe on a good day - a day earlier it was snowing and not a good place to be

The Fairfield Horseshoe on a good day - a day earlier it was snowing and not a good place to be

Ambleside, United Kingdom

“Another crazy person,” grinned the stranger who had appeared, ghost-like, a shadow from the Lakeland mist. It was a Wednesday, mid-morning, and I was exhausted.

“That makes two today,” I replied, my smile a failure, more a snarl, eyes screwed three-quarters shut as the wind, and the snow, and the hail, and the rain, buffeted anything and everything that attempted to stay vertical. “I’m the first,” I added. “You’re the second.” And then, somehow, I managed to laugh.

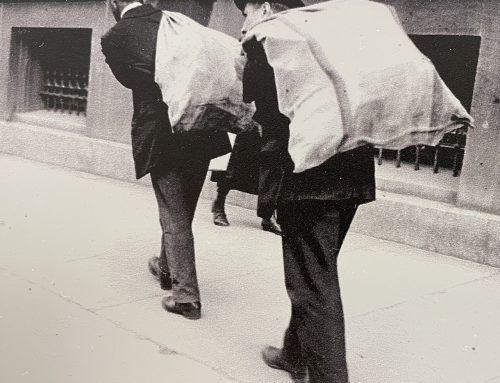

My new companion joined me, the stranger from the mist, somewhere in his mid-fifties I estimated, as he half choked on the simple humour while leaning forward on two well-used walking poles. They were scratched, twisted, battered and part bent, almost beyond recognition, but were clearly designed to last. Irrespective of his dubious poles, I could see my unexpected acquaintance welcomed the rest.

“You going the whole way?” I asked. The Fairfield Horseshoe, a classic circular walk from the town of Ambleside, beckons many when the sun is shining, far fewer when the weather is bad. The Horseshoe does not sound difficult. After all, it is only 18 kilometres long. It is the more than 1000 metres of climbing, the weather and the going underfoot that makes it different. Today had been one of those days when it had been hard to decide. Go? Not go? Stay in bed? I had glanced from my front window in the heart of Ambleside, the moment I had awoken around dawn. One look at the mountain skyline and I could see it was mainly clear. Early morning cloud had touched just beneath the summit. I was sure it would be gone by lunch, so the Fairfield Horseshoe was a goer, and I had set off with intention to my step. I was wrong, of course. By mid-morning the sky had descended, the wind had picked up and Mother Nature was reminding me that mankind can never be boss.

“Aye. I’ll be going the whole way,” came the reply from my unintroduced companion who was going up as I was going down. “What’s it like up there?” he asked.

“Not bright,” I answered, realising that I was in the land of understatement. This was not the time to give detail of my recent rookie attempts to navigate my way out of imminent disaster as I had rounded The Corner of Fairfield Horseshoe. The Corner is what the locals call it and is formed by a series of peaks. Link Hause, Scrubby Crag, Hart Crag, Dove Crag, portions of mountain with wonderful names but which cause those with experience to glance up, listen and look doubtful. The Corner is where people perish, where walkers are lost, where bodies are found. The Corner, barely two kilometres in length, is where all are advised to be careful. It is not where you want to be in bad weather and yet The Corner was the stretch I had just passed.

It had not been simple. By the time I had reached it, by the time I realised I had made the wrong call by taking to the mountain at all that day, I had walked too far to retrace my steps. Better to navigate my way forwards than struggle to find my way back. Satellite navigation in one hand, compass in the other, map dangling dangerously from my neck and whipping viciously in the gale, this was not an occasion to fail. Wind chill was easily horrific, all feeling had gone from my nose, visibility was near zero with snowy wind slab cloaking the ground. I could see icy deposits hanging like magnets to the hairs on the back of my hands. For a moment I had panicked; that welling up of fear. Was this how people died on mountains? Was this the way it would end? Yet had I screamed, yelled or shouted, there was no one nearby to hear me. I was filled by the realisation I had broken all rules. I was alone, no one knew my route and a mobile signal was a non-starter. It would take them forever to find me. I had to get it right.

For a moment I had hesitated. The Corner makes you do that. It is a place on the route where you are forced to think. Should I stop and glug the warm black tea from the flask in my rucksack? Maybe munch the bar of chocolate positioned at the very top of my pack? Good thought perhaps, but to eat and to drink meant stopping, getting colder, becoming wetter, soaked through to the skin.

Gloves! You retard. Why are you not wearing them? Only idiots walk the Horseshoe in winter without cover from head to toe. And me, I should know better. Many years earlier I had acquired three black fingertips while climbing America’s highest mountain. Yet here I was now, prancing around England’s Lake District bare-fingered because that is what touch-screen navigation devices require. What a buffoon. Ungloved hands are fine in the sun but try them when your screen is covered by running water and your fingers are too cold to do anything other than shake. The Corner had been an epic and I was lucky to make it through. The Reaper so nearly had his day.

I looked again at my Cumbrian companion, for he was clearly local. That much had been evident from the few words he had spoken - his accent, his stance, his expression. He looked tough, as well. The Cumbrians have been a warlike people for generations and once belonged to Scotland, which is why they do not feature in the Domesday Book of England and parts of Wales. Cumbrians are strong, not prone to exaggeration, yet their only failing is the broadest smile whenever it starts to rain.

The wetter a Cumbrian, the happier they appear. “Good morning!” shouted the young woman in her early twenties, as she had jogged past me on an Ambleside pavement shortly after dawn the day before. I had been out and about, unsurprisingly in the rain, for an early-morning stroll, inhaling deep gulps of Lakeland oxygen with each step. “Lovely day, don’t you think?” the jogger had added as she trotted past, seemingly without effort.

“For sure,” I had replied, shouting after her, while feeling envious of her youth, impressed by her fitness, but puzzled why she should appear so happy. Moments before I had seen her soaked from head to toe by a speeding lorry that had gone straight through a deep puddle in the gutter and sprayed her athletic frame full on. She had not twitched a muscle. No swearing, no angry signs, no hesitation. It was as if the soaking had not happened, that being drenched by lorries was a Cumbrian hobby. She had smiled, broadly too, and had continued running, something she clearly did every single day. A full-thickness soaking was apparently normal for this Lakeland jogger.

And here, back on the Fairfield Horseshoe, in the rain and the mist and the snow, my new companion was also smiling. What happy pills, please, are these Cumbrians taking? I’ll have some by the ton. Granted it was a doubtful smile, but a beam nevertheless. Then I saw him push himself to the vertical using the sticks impaled in the mud, brace back his shoulders and look upwards at the near-invisible mountain before him, which was still shrouded densely in mist.

“Somewhere up there is it?” he asked, demonstrating perfectly the Cumbrian motto of Ad Montes Oculos Levavi (I have lifted up mine eyes unto the hills).

“Yep,” I replied. “Keep going. You’ll not miss it. Just be careful at The Corner.”

“Ah, that place,” said the stranger as he took his first step. Then he hesitated briefly, looking back in my direction. “Yes, The Corner,” he added, once more the nod. “Well you made it, so might I.”

With that he was gone. No map, no compass, no technology. Just a Cumbrian, two bent poles, and bad weather on a mountain.

Snow changes things when you are climbing

Don't forget your gloves on a mountain