Jet lag – why do you do these things?

Jet lag - why do you do these things

Jet lag - why do you do these things

San Francisco, USA

Each time I travel I pretend I am immune and each time I journey it catches me. Most call it jet lag. I call it, quite simply, brain/time disconnect.

Travelling to San Francisco is a classic. Eight hours, yes a full eight, of time difference exists between Brit and Yank. Night becomes day, day becomes night, and my body hasn’t a clue. The hotel’s gym demonstrated this perfectly in a way that perhaps I had best explain.

The other morning, two days into my US trip, I awoke from what I was sure had been a full night’s sleep. I glanced at my watch in what I took to be the early morning light, only to read - if my ageing timepiece’s faded luminescence could be trusted - that it was 2 a.m. That is an obscene hour by any standards unless you happen to be a night worker or a surgeon on trauma call. It is a time of day when I am certain most of mankind is in shutdown. I could not believe it, my disbelief made worse by the way I felt. I was not dozy at all and was on the verge of being ultrachirpy. You see Nature and my physiology told me it was 10 a.m. but my watch said something different.

Flummoxed, my first step was the telly. I fumbled about in the half light, which by then I realised was not a dawn glow creeping past the curtains but the distant green glimmer of my razor’s charging light. It made everything seriously spooky. All it needed was a poltergeist and the scene would have been complete. With the palm of my right hand I patted the surface of the bedside table and determined not to turn on the lamp as to do so would be the final acceptance that sleep had ended. Somehow I had to keep a hold on slumber. There was no logic in feeling that way, it was just that at 2 a.m. it seemed sensible. How often that has happened on my travels and this occasion was no exception. Whenever I pat down bedside tables in the dark, any sense of co-ordination vanishes. First my glasses hit the floor, then my notebook, always my mobile telephone and, on this occasion, a large glass of water that overnight had lost its sparkle. There you have it, the first sign of jet lag, which is a clear inability to feel anything other than frustration in the dark.

Eventually, after much scrabbling and a bedside floor littered with possessions, I found the rectangular telly remote. In a typically US way, the remote was plastered with buttons, each too tiny for anything other than a neonatal finger, although I guess a chimpanzee might have been able to cope. The remote was a perfect rectangle, not tapered, with buttons front and back. I turned it this way and that in the dark, as I did so trying to remember whether the on/off button was round or square. Or, for that matter, where it was to be found at all. Yet however I angled the remote, wherever I pointed it, nothing happened. There was zero response, not the tiniest flicker. A dead battery? Sadly not. Just me being hopeless.

I gave up in the end and flicked on my bedside lamp. This was no lamp, I realised instantly, this was a life experience. Its glare made an interrogation spotlight look like a candle. It was bright, so bright I was sure I saw steam rising from the shade. Then, unannounced, a brief fizz and a startling crack, the light flicked out. Its bulb was jet lagged, too, and had reached the end of its natural life. The bulb had behaved exactly as I felt.

Before the lamp’s last gasp, it had given me just enough time to establish that I had been pointing the remote not at the telly but at the telly’s reflection in a desk mirror. The dying bulb had also given me time to recall that the on/off button was round, big and red and the only button among umpteen others that had sufficient size for a British early-morning thumb. So I pointed the remote now accurately at the telly, pressed the big red button and watched the laborious sequence of flashing lights take hold. Menu pages, ghastly pipe-like music, scenes of young couples walking up and down beaches hand in hand appeared and disappeared until the opening sequence stopped, reaching a point when I had to press another button on the remote for final channel selection. Not a hope. There were so many buttons and whatever I next pressed, there seemed to be zero response from the telly. There was only one thing for it. I would have to get to my feet.

So up I got, any semblance of sleep now well gone, and staggered across to the far corner of the room, stubbing both little toes against items of furniture in the process. You feel such a fool swearing at yourself in the darkness especially when there is no one to hear, but swear I did.

I let my extended hand scrabble for the door jamb. Had the light switch been to the left or to its right? I remembered wrongly, of course, so a seeming age later, though probably little more than a few seconds, I was squinting in the bright light of my room. The Master switch I had pressed spared no mercy. Every light went on, apart from the still steaming bedside lamp, leaving me starkers, confused, eyes screwed up in pain, and with two agonising and throbbing little toes. The telly remote had barely survived and was now listing at some hopeless angle while held tightly in my clenched right fist. Slowly I let my eyes open, blinked, shook my head and looked towards the telly. The thing stood there inertly, apart from a tiny red light at its bottom right corner. So I adjusted the remote and held it purposefully, threateningly almost, at the telly. I was a man on a mission. For a moment I hesitated and then I pressed the number 10. Well actually I did not press ‘10’ as there was no such button. Anything over 9 needs a two-button press, 1 followed by something different. Believe me, pressing one button is bad enough when your body is eight hours shy of normality. Pressing two is an impossibility; another problem of early morning jet-lagged remotes.

I cannot remember how I did it, but almost with a trumpet fanfare on went channel 10, up came CNN and after a brief lag, onto the screen appeared two familiar faces that I must admit I am learning to dislike. It is not that they are nasty people, far from it, they are good. It is not that they are reporters. That is a profession I support. No, it is because they were so jolly. How can anyone be so jolly at that time of day? There was me feeling like death, staggering around my hotel room with two sore toes while there were two smiling faces filled with life, enthusiasm in everything they said. There was certainly copious chit-chat. I do not think I am alone when I say that you do not want jolliness when you are jetlagged. You need peace, quiet, understanding and a gradual introduction to your new environment. This allows you to wander about pretending to be normal, when clearly you are not. You fall asleep in meetings, certainly in lectures once the lights are down. You lose your way when map reading around town. You want to eat when restaurants are closed and want to sleep when they are open. You arrive for events frighteningly early, or sometimes embarrassingly late. Jet lag, oh jet lag, why do you do these things?

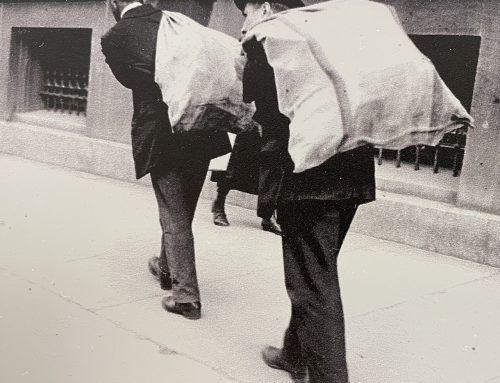

My telly viewing did not last long. The enthusiasm of the presenters was more than I could handle. Anyway, by then I was properly awake, there were at least five hours before my first programmed engagement, so what the Hell, why not go to the gym? So I did. I let myself out of my room and headed down, down, down into the bellows of the hotel. Gymnasia seem often to be placed as far away as possible from sleeping accommodation, I imagine thanks to the noise, sweat and odour they create. However, at this hour, shortly after 2 a.m., the hotel’s corridors were deserted. There was not a solitary form of life, just the inevitable canned music exuding from hidden speakers and playing something verging on flamenco.

It was as I drew nearer to the gym, following signs to Fitness and Spa, that my suspicions grew. What was that noise? It was a distant clattering, a sort-of monotone hum. Surely not? I could not believe it. But as I turned the final corner and allowed my magnetic key card to click open the gymnasium door, I could see it was not my imagination. The gym was full. By full I mean to busting. Every treadmill - there were at least eight - every bike, every cross-trainer and rowing machine. The place was heaving and there were still four hours until breakfast.

Gymnasium etiquette demands that you pretend you are alone even when you are not, ignore your companions, and stare into the distance, maybe at a screen, or even into a huge wall-length mirror before you. What you do not do is acknowledge anyone else exists. Yet as I glanced around I could see several familiar faces, colleagues who had made the same long journey as me. They, too, had clearly encountered jet lag. They, too, had probably been staggering around their rooms in the dark. For all I knew they had sore toes as well. And they, just like me, had decided the gymnasium was the best place to visit. The best way of encouraging physiology to make Nature’s rhythms feel normal when, in reality, they are anything but. Jet lag, oh jet lag why do you do these things?

The hotel gymnasium - never acknowledge others exist.