The error of abandoning reconstructive surgery for the war-wounded

Tripoli in northern Lebanon and home to essential reconstructive surgery

Tripoli in northern Lebanon and home to essential reconstructive surgery

Tripoli, Lebanon

As an orthopaedic surgeon who has undertaken more than a dozen ICRC missions to the Middle East, I was horrified to hear the organisation was proposing closure of its reconstructive programme in northern Lebanon. Surely, I thought, they must be joking? Sadly, it appears not.

In 2014, ICRC opened its Weapon Traumatology and Training Centre (WTTC) in Tripoli to help the chronically war-wounded. It now admits patients from Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Yemen and beyond. Its creation was a courageous stroke of genius by the ICRC of that time, as to focus on the long-term medical effects of war wounds, and there are plenty, was far outside what the ICRC normally handled. It was an area of humanitarian practice that had been ignored. The only other place in the world that came anywhere close, was a similar unit run by MSF in Jordan’s Amman. WTTC has now treated more than 2000 patients surgically, undertaken over 2700 treatments of mental health, has a thriving rehabilitation facility, and has screened almost 2500 patients from throughout Lebanon. It teaches, trains, and publishes research, has been judged as highly cost-effective, and does all of that with roughly 60 local staff. Its achievements are remarkable.

I realise that WTTC is expensive - US$7 million annually is a lot of cash - but when seen alongside a global budget of US$2 billion for an organisation that employs 20,000 people in 80 different lands, maybe WTTC is not so costly. Are there not other projects that might be closed, and simpler to re-establish? After all, plenty are already handled by fellow organisations. WTTC is unique, in the true sense of that word, and has developed an expertise that the world respects. There is no going back should WTTC vanish.

I form part of a loyal group of specialists that has helped put WTTC where it is today. Some say that without us, little would have happened. The surgery I have performed has been highly complex. Many of the patients have undergone multiple procedures by other surgeons in far-flung lands before they ever reach WTTC. War wounds frequently become deeply infected, so WTTC has amassed an almost unrivalled experience in the management of these problems. The surgery, and associated bacteriology, needed to deal with such difficult cases must be the best of the best. This is now, I feel, what WTTC can offer. These are not cases that can easily be transferred to others and I worry what will happen should WTTC close. No one has sought my view, indeed officially I have been told nothing. As best I can establish, my colleagues are equally in the dark. Mind you, perhaps I was not asked because them-up-there, whoever they may be, predicted my answer.

The complexity of the cases means that WTTC addresses an area of medicine that is outside the normal. For those accustomed to routine humanitarian practice, especially if they are non-medical, WTTC is difficult to understand. I worry, too, that any decision to close WTTC may be because those responsible simply do not comprehend. How much easier it is to say, “No” than, “Yes.”

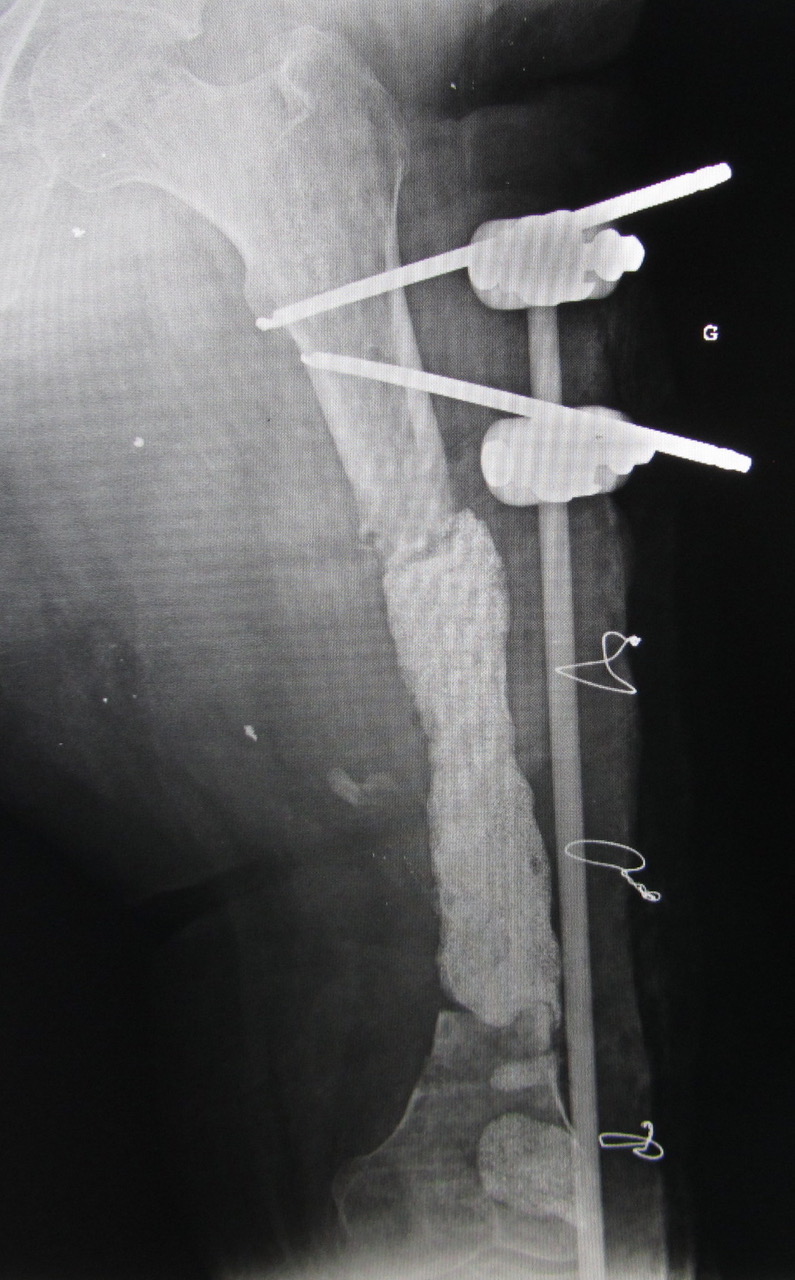

Initial surgery for a war wound may save life and limb but when up to 80% can become infected, further operations are inevitable, with each procedure being more complex than the one before it. After wounding and their early surgery - some have had up to ten previous operations - if the opportunity arises, patients will travel great distances to reach WTTC. Most have had adventurous journeys.

At WTTC, they can receive similar care to that on offer in major teaching institutions in other parts of the world. Keyhole surgery, bone grafting, joint replacement, advanced plastic surgery, and so much more. The work WTTC has done to resolve these cases has been nothing short of miraculous. The unit is about saving livelihoods, as well as lives, and giving the unfortunate a future.

The patients’ stories have frequently been remarkable and often unexpected. I have anonymised them here for obvious reasons.

The 15-year-old boy who had been shot through the hip through no fault of his own. Sadly, I did not achieve a full cure, but I did develop a bond, and by his discharge he had decided to become a doctor.

Or the 18-year-old girl whose thigh bone had been destroyed. Could I repair her, asked the widowed mother, because her daughter was the only source of income?

And the 82-year-old grandfather who had struggled on foot across the mountains to reach WTTC, with his damaged pelvis.

“I didn’t get to 82 by being a weakling,” he said, almost in passing, when I commented on his journey.

WTTC, in a short time, has built an experience that nowhere else in the world can boast. Its specialists teach widely and are in huge demand on the global stage. For me, it has been a privilege and honour to be involved. And should WTTC close, what will I do? Carry on, of course - teaching, operating, encouraging, researching, just as I am now. I will simply not involve a truly wonderful WTTC. My colleagues will likely do the same.

Consequently, to hear there have been thoughts, even decisions about its closure, and what that means for patients, staff and the wider world, has kept me sleepless. I want to be there, I want to help them, yet I know I cannot.

The other day I wrote to a well-known ICRC figure.

“If you do close the unit,” I said, “in the years to come and perhaps once you have left ICRC, those of you who have formed part of the closure will hang your heads and say, “Oh dear, we should not have done that.” By then it will be too late.

I received no reply.

Operating in Tripoli

One of many complex issues that a war wound can create

Tripoli is not a wealthy place