Eating to stay unhealthy

Baklava at Hallab - you can keep munching and chomping for ever

Baklava at Hallab - you can keep munching and chomping for ever

Tripoli, Lebanon

Tell me, please, how four fully grown adults, some more ancient than the rest, can resist temptation? I may be aged a million, I may have wrinkles three metres deep, but surround me with sticky, gushy, succulent cakes and I might as well be three. When it comes to will-power, and with food I have total zero, I give way on each occasion. Diet? Me? Not a hope. Just think what I would be missing.

It was Hallab 1881, somewhere near the centre of Lebanon’s Tripoli, a family business that began in the year of its name, and our group of four was hunting for what was touted to be the world’s best baklava. Hallab 1881 carried the crown and attracted travellers from throughout the globe, especially Beirutis at weekends, so Hallab it had to be. One glance at social media and you would conclude that the only purpose for going to Lebanon was to overeat at Hallab.

The baklava, that pastry made from layers of filo, stuffed with chopped nuts and swamped with syrup or honey, was our reason for seeking out Hallab. The baklava’s origins are hotly debated but Turkey’s 17th-century Constantinople probably wins, where the Sultan from the capital’s Topkapı Palace would present the Ottoman dessert to his elite soldiers on the 15th day of each Ramadan. It was called the baklava alayı, the Baklava Parade, and is a ceremony that continues until this day. Mind you, the Sultan was not overly generous. One baklava for every ten soldiers was his ration but who wants a soldier to be fat when he is looking after your life?

“Problem,” said the waiter, as we sat at a long marble-topped table to one end of the glass-fronted restaurant. Outside, the crazy Tripoli traffic, which follows rules of its own, was honking and flashing, tyres screeching, gearboxes graunching, occasional sirens blaring, yet somehow that did not seem to matter. We had found Hallab, had secured its only free table, so the noise outside made not a jot of difference.

“Problem?” I repeated, puzzle in my tone. No one had ever said “problem” to me in the Middle East before. This was a land where “No problem” was cited for just about anything, especially when things were going wrong.

“Me no Eeenglish,” the waiter continued.

“Me no Aaarabeek,” I replied, unless being able to say please and thank you counted as sufficient for ordering a pastry.

‘You wait,” said the waiter, disappearing behind a row of display cabinets burgeoning with different ways to perish. I looked at my colleagues who had joined me for the thrill. I did not have the heart to say that a single baklava, medium sized, holds 334 calories and 60% is fat. Oh dear, that is another nanometre of narrowing in a senile coronary artery. Mind you, at least I can die happy.

I can hear them now. “What were his last words?” my family would ask.

“It was a wonderful baklava,” would come the reply.

We did not have to wait long. The dark-suited head waiter, fluent in English, but whose vocabulary centred solely around Hallab’s zillion pastries, and which was best for whichever occasion, appeared beside our table, concern his expression. For a moment I thought he was giving a warning but decided instead this was a version of Hallab welcome. “You want baklava?” he asked.

“We want baklava,” we replied in almost unison, although one colleague had decided to provide supporting medical cover - and, oh boy, did we need it - by quaffing orange juice. Yet there was no smugness about his decision. All I could sense was envy. Given half a chance, he would be in there, too, munching baklava like no tomorrow.

For the remaining three of our group, the decision was easy. We would stuff ourselves beyond stuffing. We would become fuller than fuller than full. We might even down it in one. Who cares if a dietitian would allocate a hundred lines by way of punishment? What is wrong with being wicked? Is there truly any harm to a little sin?

So, for one baklava read two. Okay, three, four and five. And not only baklava. At Hallab the choice of dessert is mind boggling. Somewhere to its rear are real-time white-hatted chefs making real-time food in real-time ovens but, like the rest of humanity, talking politics rather than food. It takes only seconds for a fresh something-or-other to make it to your plate as anything you see, taste or purchase is made skillfully on site.

“Two for table six!” I heard a waiter shout when I snuck away from our table to see how food was done.

“Eight for table 11!” shouted another.

“Six for table four!” this time from a lady, complete with hijab and apron.

Hallab was full of guzzlers, that much was clear. Our table of four may have downed more than 5000 calories in less than half-a-moment, once the platefuls of everything had been delivered, but around were others making light work of plenty more. There were grannies and children, husbands and wives, maybe even the occasional lover. Hallab was not after reminding us of human frailty. It was not the place to visit should you have a conscience. Hallab trades on temptation, on weak will, and its own efficiency. Hallab’s business is joy.

So, remember, when you do eventually find the world-famous Hallab 1881, down the busy end of a busy road in an even busier Tripoli, you are not going there to stay healthy. Fill that plate, order plenty more, and allow your blood sugar to go crazy. Leave any sense of diet behind when you enter Hallab. It is simply not the way it is done.

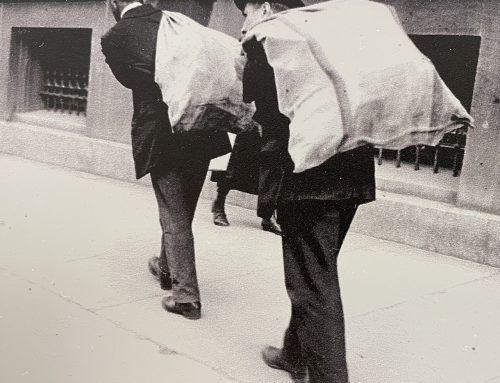

Chefs hard at work at the back of Hallab

Pastries at Hallab 1881 - try downing all they give you in one