Waiting for that killer shot

Waiting for that killer shot

Waiting for that killer shot

Dubai, UAE

When it comes to photography I am unqualified to write. Yet somehow, needs must at the moment. A few evenings ago, you would have found me in a hotel reception, somewhere in electricity-crunching Dubai, waiting for friends to join me for dinner on the town. They were late, I was bored, and then in strode the Koreans.

Dubai is the fourth most visited tourist city in the world after London, Paris and Bangkok; more than 14 million foreigners go there every year. The bigwigs are praying that number will reach 20 million by 2020. A small proportion of those are South Koreans, instantly identifiable by their cameras and that they travel in a horde of at least 50. Fifty Koreans, each with a mobile in an outstretched arm, watching a screen rather than their way, and glancing occasionally towards a guide clutching a raised red flag. I looked at the guide; she looked as bored as me. But the Korean mobiles told a story.

First my confession; I am a photography no-hoper. Yes, I can press a button the same as any other, but the image I capture is invariably suited only for disposal. I have been on several courses, read a ton of books and owned a cupboard full of cameras over at least a dozen years. The result is the same; blurred, misaligned and useless images, fit only for the bin.

Yet in the diverse parts of the world I visit, photographers are a breed I meet - plenty of them - and, how do I put it, they are different. I sense many are lonely, too. Now there is a business opportunity; a camera that can hold a conversation. But best I can tell, photographers see life through a lens or on an LCD screen and utter not a word.

Researchers have looked at this, specifically Fairfield University in New England, which tasked participants to visit an art museum and to directly observe some exhibits while photographing others. When tested later, those who had directly observed an item recalled more than those taking a photograph of the same. Added to this, the research showed that if a photographer took a general photograph, their memory of the subject was impaired. If they zoomed in with a telephoto they recalled every detail. Fairfield University called this the photo-impairment-effect, the implication being that it was easier to forget something if seen through a viewfinder than if you let your camera dangle and simply took a look.

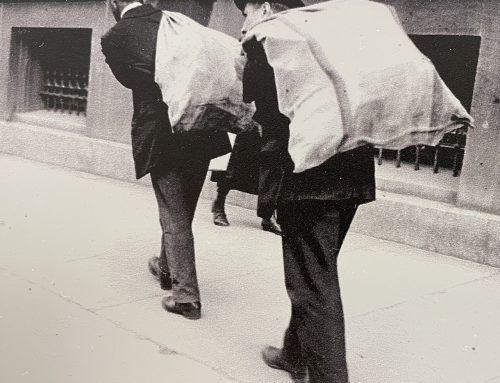

The photographers I know are also seriously competitive. It matters not whether amateur or professional, perhaps because the distinction between the two is these days somewhat hazy. Plagiarism is rife - copying others without permission - and maintaining copyright a struggle courtesy of free access to so much on line. Travelling light seems impossible and most spend their lives with their backs to the world. We see much of photographers’ backsides, we see little of their faces.

I worry also that photographers criticise each other too readily. A photograph is no longer a photograph, it is a technical exercise that colleagues seek to fault. The other day I was sat in a café, sugared Turkish coffee, my true first love, buzzing round my system. At the table beside me were three photographers poring over an image that one had taken.

“What do you think?” I heard one ask. He was manifestly proud and excited by his photo, the tone of his question clearly seeking praise. Had he been a dog his tail would have been thumping hard against his white and rickety plasticised chair, which was well beyond its sell-by date. The clickie, for that is what I call photographers, was waiting for the compliment. Craning my neck, I looked across at what I regarded a brilliant photograph. His scene of a camel at a desert oasis - clear blue sky, perfect sand dunes, an artistically positioned palm tree and a camel looking right at me, dead centre - was almost poetic. In my world, it would have gone straight onto a living room wall, although these days more likely a screen saver. Yet something prevented me from speaking. Maybe it was the clickie’s companions, both unshaven and crew-cutted roughies who did not encourage conversation from unrelated strangers. Silence seemed safer and I am glad it did.

“It’s OK, I suppose,” I heard one of the roughies state doubtfully, as he pointed with a calloused and nail-bitten forefinger towards the bottom of the picture. Then the hesitation, “But…but…there’s something about the layout and…yes…wait…look at the focus down there. Is that bit of dune slightly blurred?” The critic looked up at the photographer, whose spirit was already fast depleted.

I sensed the photographer was about to respond when the other roughie interrupted. Grabbing the hard-copy print, the roughie pulled it across the table towards him, rotating it forcibly to take a closer look. “Yeah!” he exclaimed, “I thought so! It’s red eye, bleeding red eye. I didn’t realise camels got red eye, did you?”

With those words, the clickie had become history. Had he been a balloon he would have been flat. Sensing an imminent punch-up, I stopped my neck craning and turned back towards my half-finished Turkish coffee. I almost missed the clickie rising to his feet, gathering up his prize image in one movement and tucking it under his arm.

“See you later, guys,” I heard him mutter, disappointment, nay tragedy, in his tone. With that he turned on his heel and was away, shoulders hunched, feet dragging.

Clickie gone, it was the first roughie who broke the silence.

“That was sudden,” he declared, “did we say the wrong thing?”

“Course not,” replied his companion, “we were just giving feedback. How else is he going to improve?”

Critical to each other photographers may be, but obstructive to each other they are, too.

There was me some evenings back, on a bridge near Dubai’s Burj Khalifa, watching two photographers battle for that once-in-a-lifetime sunset shot. Clickie One, the first to arrive, was perfectly lined up and waiting for the killer photo that would instantly go viral. Then into view walked Clickie Two and started setting up his tripod.

“Whoops! I’m sorry,” said Clickie Two, feigning surprise, “I didn’t see you there. Am I in the way?”

“Yes, rabbit head,” came the embittered reply, “you could not be more central.”

Rabbit head, I remember thinking? Now there’s an insult I had not heard before and which I should lock away for some future occasion.

By the time the two had sorted out their difference, with Clickie One going left and Clickie Two going right, the sun was beneath the horizon and the killer shot had flown.

Time, I sense, for groups of clickies to have umpires thrown in for free. How else can you stop photographers arguing?

It is hard to travel light as a photographer