The F-word

Hands are valuable items to a surgeon. You want to watch where you put them.

Hands are valuable items to a surgeon. You want to watch where you put them.

Beirut, Lebanon

She stuck it in, I wanted it out, but I had already stuck it in myself. The result? An excellent job and I barely felt a thing. Dear me, I can see what you are thinking so perhaps I had best explain.

You see, it started with an operation at lunchtime. One of those long procedures that you think will take an hour but takes three times as long. Surgeon time is as unreliable as it gets. If you think something will be quick, it will be slow. If you think something will be slow it will be quick. There is also a superstition, certainly held by me, to never say an operation is going well until you reach the end. It is as accurate as driving through a capital city and declaring the streets traffic free. The moment you utter those words, around the corner is a ten-mile tailback. That is the way of surgery.

From beginning to end of any operation, a surgeon is a hair’s breadth from disaster, which is why medics are forever missing dinner dates, appointments and all things in between. It is also probably why 60% of surgical marriages fall apart. No spouse other than the most tolerant can understand why their other half is repeatedly late returning home, can never make it away at weekends and, when actually at home, spends most of the time asleep. In a way, a surgeon is being unfaithful. Most colleagues I know have two spouses; there is the living one at base while the other is the operating theatre. If anyone needs a Long Service and Good Conduct Medal it is the spouse of a job-obsessed surgeon. No medal for the surgeon, of course, as the job itself is enough; let’s face it, surgery is fun. But a big shiny accolade for the spouse who may be at home, increasingly the workplace, and wondering what on Earth is going on.

Anyway, I had just reassembled a patient’s hip, it had not been easy, and was beginning to relax. I could see the end in sight. The patient was a pleasant chap, slightly more than 70, grey hair, grey beard, slightly paler than many and as Arab as they come. He also had two wives, just like a surgeon, although they were the real thing. When I had first seen him in the clinic some time before, the two ladies had been sitting beside their husband, one left, one right. They had looked totally happy with each other’s company, smiling, giggling, truly at ease and talking to one another rather than their spouse. The poor fellow had looked exhausted and for a moment I had thought his desire to undergo surgery had more to do with escaping a twin-wife marriage than anything untoward with his hip. Fortunately, one glance at his X-rays and I could see he was not fibbing. The joint was all but destroyed and becoming more so by the moment. Someone had to do something and thanks to a brief humanitarian attachment in Lebanon, with mankind busily destroying itself just across the border, that someone had been me.

For big operations, such as sorting wrecked hips, patients do bleed. I still await that magical moment when someone will invent a bloodless operation but realise that occasion may be many decades away. Not a hope with a hip. The thing has blood vessels everywhere so bleeding is an occupational hazard, for both surgeon and patient.

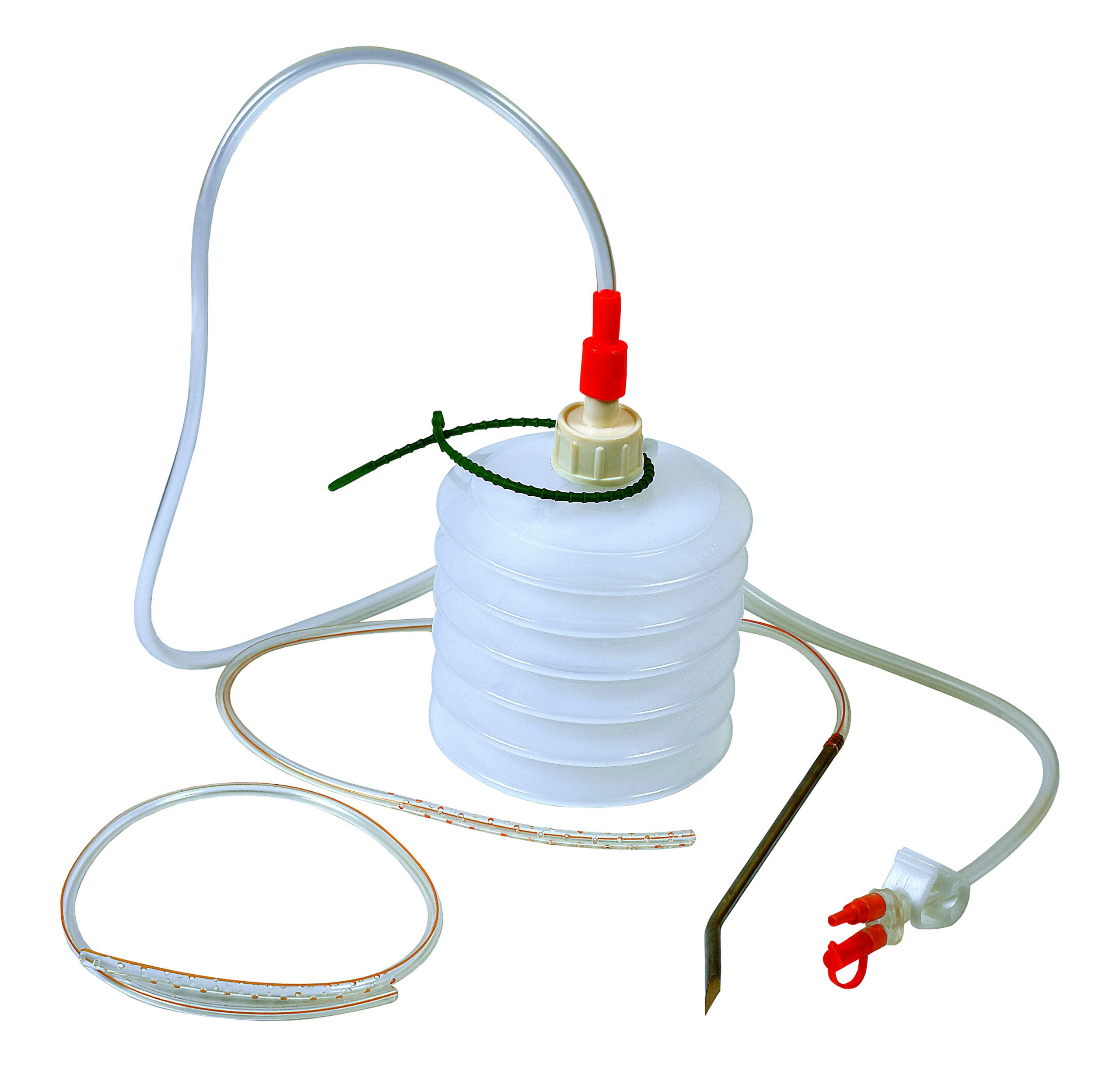

You can stop most bleeding, but not all. Sometimes you simply let it happen, which is why things called drains are used. These are small plastic tubes that a surgeon leaves behind after an operation and which mop up the remaining red stuff. But a drain must be put in place by hand, it does not get there by magic.

You insert a drain with something called a trocar, and that is where the trouble began. There was me, towards the end of the operation, and tired. Get it? Surgeons are human, too. I was knackered. My trocar was short and stubby, not long, thin and curved as was usual. It was straight, it was shiny, almost threatening, very unwieldy, with a tip so incredibly sharp it could slice through anything. And it did. As I pushed it through the patient I shoved it through my thumb. No, I do not mean in, I do mean through. You could have heard my yell in Cyprus. I think they probably did. The theatre complex came to a halt, the traffic noise from outside seemed suddenly to vanish, while the Lebanese Army was surely put on alert. I could only thank my Maker that the Arab staff, bar a few, could not understand my expletive. Those who did tried hard to suppress a giggle. I was not giggling at all.

They call this a needle stick injury, despite the trocar being many times broader than a needle and about the size of a pen. I call it an assault. Regardless of definition, instantly I was hosing blood and any relaxation vanished in a nanosecond. But here is the catch. When you stick an instrument into yourself during an operation, however unintentionally, you are exposed to the blood-borne diseases your patient may have; meanwhile the patient is exposed to yours. An incident is declared, the administrators are involved and, oh dear, once that happens your moment of inattention becomes a sequence of events that can continue for hours. At least it did for me.

First stop was to prevent my imminent demise from blood loss by sticking superglue on the holes - perfect first aid for those not in the know - an act I preceded by running my injured thumb under a tap of rushing water and turning the basin outflow a paler shade of pink. I was then handed a pile of forms by the administration. My near-death experience with the trocar was about to become Death by Form. You do not injure yourself in private as a surgeon, particularly should you holler the F word. The forms ask why, how, where and who, yet nowhere could I find place for an expletive.

And then, and then … well… and then comes the therapy. First there is the touchie-feelie session by someone who says they are trained. The gaze-into-your-eyes expression to be sure you will not implode. I am unsure if I passed that test as however much I grinned - no way was I confessing to a humdinger thumb and the fact I had already ruined one shirt through intractable blood loss - the administration response was disbelief.

Then came the crunch.

“Now you know you can acquire Hepatitis and HIV?” The adviser - she was attractive, fit, and gazing into my eyes as would a military interrogator seeking to make a prisoner crack.

“Me?” I brought my right forefinger chest height, surprise as my expression. “Hepatitis? HIV?” I looked left and right in the hope there was someone else in the room. We were alone. If you discount my colleague, that is, who was trying hard to suppress laughter by playing with his digital camera. He knew what would surely follow.

“I think you need an injection,” said the adviser.

“No.”

“Yes.” Now there was worry in her tone.

“No,” I said once again, trying to be assertive but lacking conviction. I looked up from the floor, it was dirty anyway, and gazed back at my adviser. Her eyebrows were raised and, for a moment, I thought she was upset. I glanced at her right hand. The fingers were wiggling ever-so-slightly, fingers that were not going away. At least not until they had done what they had come for.

Briefly, I felt the expletive returning but held it in check. The F-word would be inappropriate, misjudged and mistimed. Worse still, my adviser spoke English fluently and would easily have understood.

“OK then. Give it to me. The injection. Might as well.”

So she did, my colleague grinning broadly, the digital camera whirring ostentatiously as evidence of the event. I took it like a man, of course. Apart from the screaming, the shouting, the being held down, the kicking, the writhing, and the insistence of a Good Behaviour Badge when all was complete. The lesson? If they wish to stick it in you, let them do so. You can always take revenge later.

Oh yes, and never use the F-word, whatever the desire. Somehow it never seems to fit.

See that sharp thing in the foreground That's the trocar and can make mincemeat of a thumb (www.suru.com).

Surgical instruments. Try to stick these in the patient rather than yourself.