Not a good day

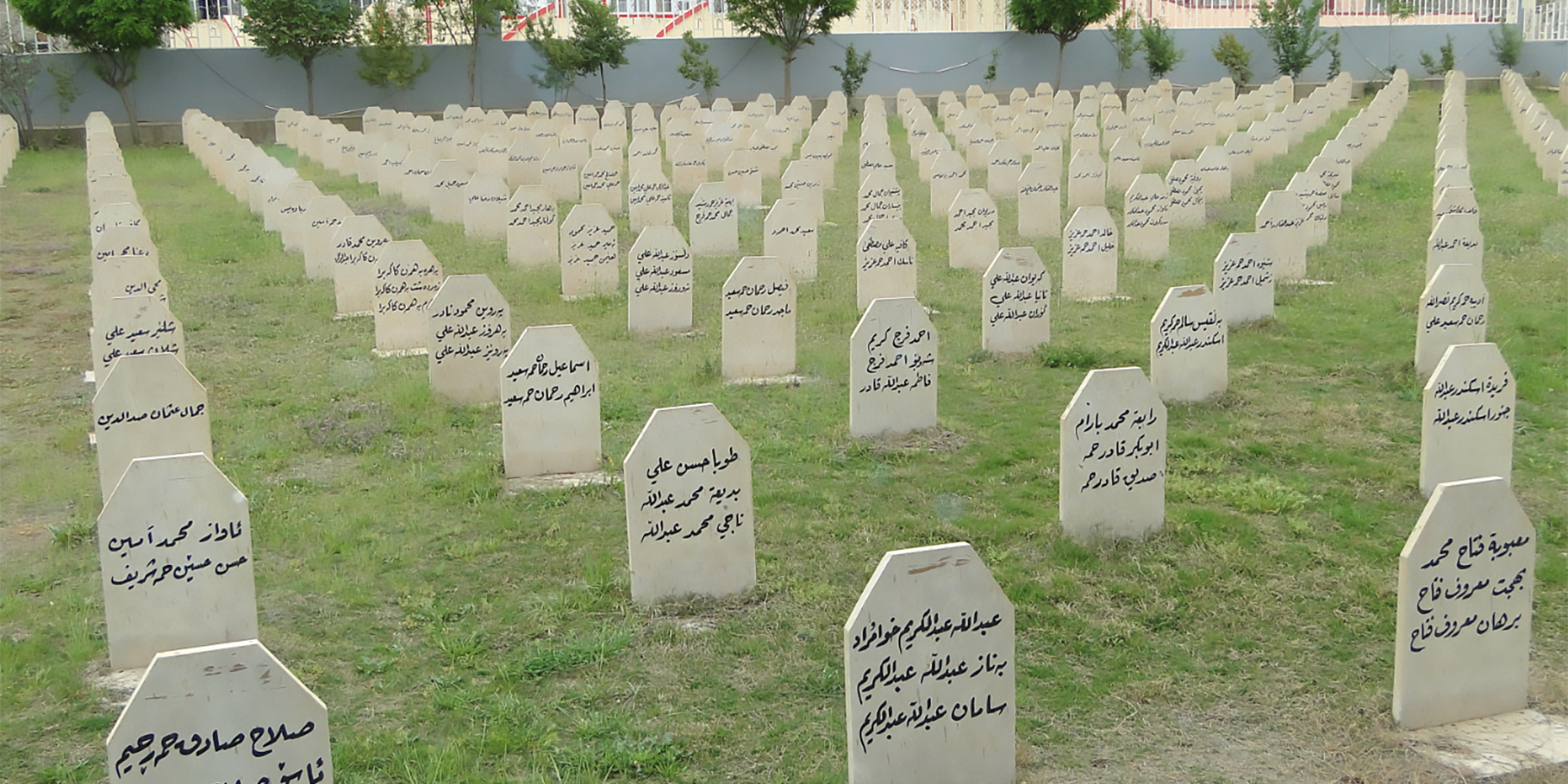

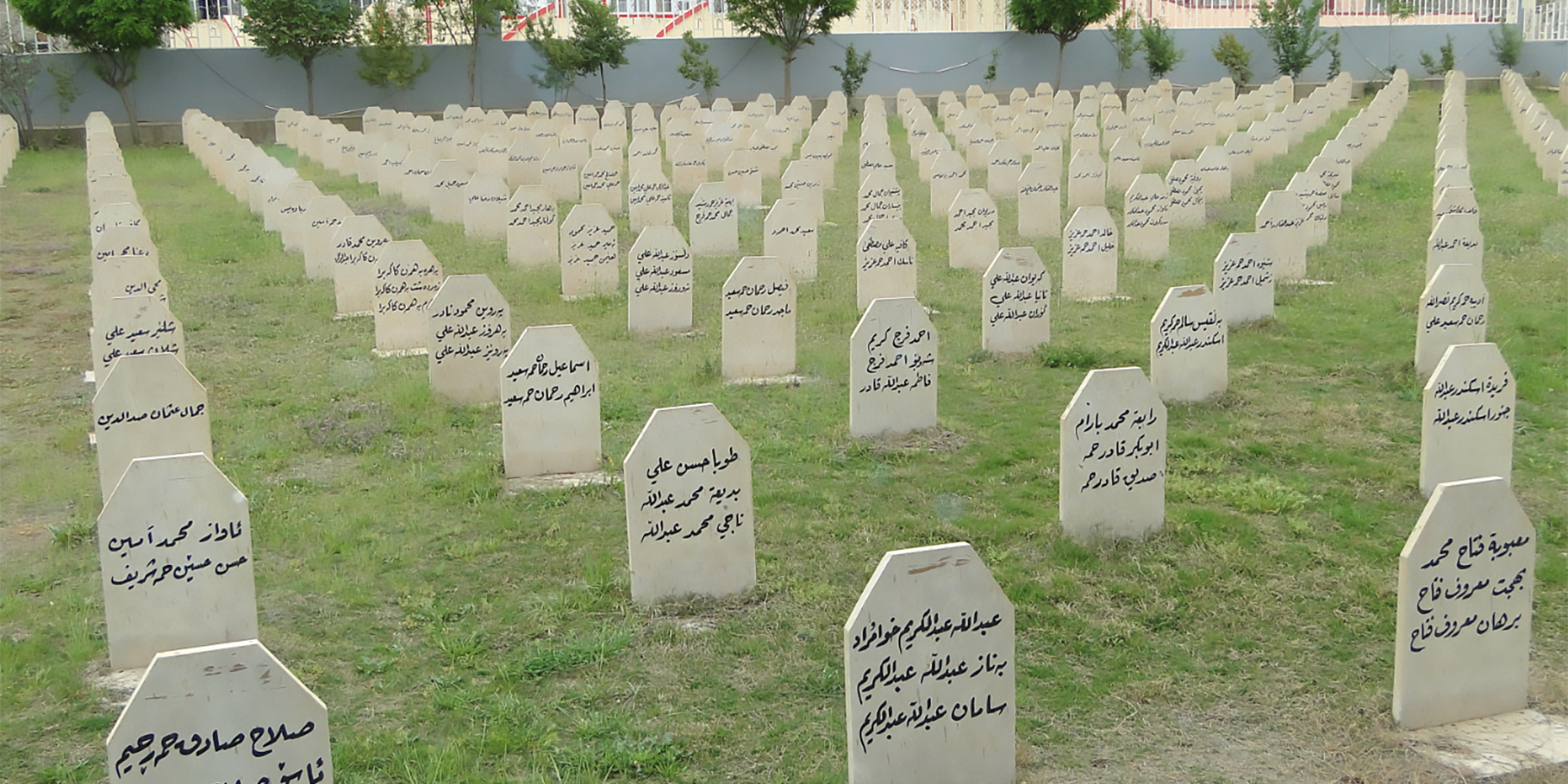

Halabja victims of the 1988 chemical attack.

Halabja victims of the 1988 chemical attack.

Sulaimaniyah, Iraq

Generally, members of my family have not done well with the Kurds. Years back, when I should have known better, I was one of three young men following a road diversion through north-eastern Kurdistan, in a grey, clapped-out Volkswagen Beetle. I was somewhere near Mount Ararat of Noah’s Ark fame. Rounding the corner of a mountain dirt-track road at breakneck speed, minds firmly in neutral, our small team slid to a halt in front of 40 villagers who were standing across and to each side of our path.

No problems there, I thought, relieved not to have run over a Kurd, until I saw that each was armed with a stone. Come to think of it, stone is the wrong word. They were rocks. Huge, sharp, angular, rough, threatening, and seeking to do us harm. Our driver, an engineer, instantly panicked and stalled the car. I will not repeat my language. Yet we did escape, somehow, by luck and zero judgement and stuff of a further tale. The car, however, carried wounds that stayed with it until the scrapyard. I carried scars that stayed hidden, supported by a passionate, secret promise that I would never return to Kurdistan. It was not a good day.

So much for the Turkish Kurds. Maybe their Syrian brethren would be kinder, this time not to me but to another member of my family who headed out their way. Sadly not. Within a week of his arrival in Syrian Kurdistan, the war in full spate, he was forced to escape for his existence. Accused of suspicious behaviour, maybe far worse, the noose or beheading beckoned. The survival gene came into play - critical if you intend to visit war zones - and he was back across the border to safety quicker than you can say jihad. It was not a good day.

Time to move on I think, as Turkey or Syria had nearly done for us both. So, this time it was Iraq. Life could surely only get better? It had to be something seriously impressive to make me break a pledge and it was manifestly a weak moment when I accepted.

“Want to come?” came the invitation. My colleague is Kurdish to the core, a real charmer and one of those you cannot reject.

“Must I?” was my answer, before telling him this would have to be third time lucky.

“No problem, let me show you,” he replied, a brief smile, a nearly imperceptible nod, and somehow I had agreed. At least it was Iraqi Kurdistan, I reflected, not Turkey, not Syria. Maybe, just maybe, this would be different.

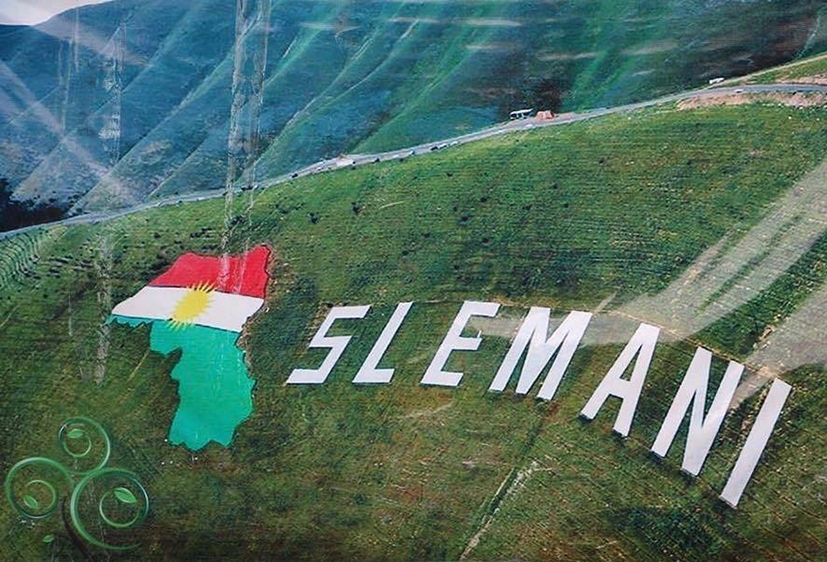

So Sulaimaniyah it was, the cultural capital of South Kurdistan and known as Slemani or Suli by the locals. It is a city of roughly two million souls, which has set itself apart from the rest. A major draw for Iranian tourists, Suli houses the second largest museum in Iraq, second only to Baghdad, and is closely allied to the west, at least in terms of behaviour. Its university has probably more women than men - few of the ladies wear the hijab - and, joy upon joy for me, the place is surrounded by mountains.

Suli was founded in 1784 by a Kurdish prince, Ibrahim Pasha Baban, who called it after his father, Sulaiman Pasha. It is a cultural Mecca - writers, artists and poets abound - although sadly the bad guys like it also. It knows how to rain, too, big time. Blue skies? Maybe, but you could have fooled me.

Yet one thing strikes you hard in Suli and that is the Kurds are different. I knew that already, of course. They can throw a rock with unerring accuracy. Yet they are so different I am astonished they have yet to declare independence. After all, the four Kurdish regions - Iraq, Syria, Turkey and Iran - contain more than 30 million inhabitants. This is the world’s largest population without a country. Sadly, that means trouble ahead. Indeed, I cannot see how it can be avoided. Look from your window in central Suli and on the mountainside before you is the local equivalent of a Wiltshire hillside white horse. It is the Kurdish flag, red, white, green and yellow, in the shape of the desired Kurdistan. The Kurds want independence passionately. It is the sole topic of conversation for many.

My guess is that one of three things will happen, each of which will end up with independence. Top of my list is that the current conflict will continue, but for Baghdad, which officially runs Kurdistan through the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) in Erbil, to continue falling apart. The weaker Baghdad becomes, the stronger is the KRG. It sounds much like Scottish Independence although to be fair to the Salmond-Sturgeon axis, they have not resorted to bombs. Yet the slow attrition of a Baghdad mothership, which is taking place daily, might allow an independent Kurdistan to appear, as if by magic.

Perhaps a better option would be for independence to be granted after long, drawn-out discussions with Baghdad. That might be better for the other countries, too, as they would have more time to become accustomed to the idea. But whether Baghdad would agree to independence is anyone’s guess and, I would suggest, unlikely.

Look at what Saddam Hussein did to keep the Kurds in control. His Al Anfal campaign in 1988 was said to have killed more than 180,000 Kurds, with another 25,000 annihilated in 1991. More than 2000 villages were razed to the ground. “Anfal” is a Koranic word that means “the spoils” and described the campaign of extermination of non-believers by Muslim troops in 624CE under Ali Hassan al-Majid. Now come forward a further umpteen years. Heard of Halabja? If not, you should have done.

They call it Bloody Friday, 16th March 1988, when multiple gaseous agents were used against a largely civilian population - mustard gas, nerve agents and possible hydrogen cyanide. The common feature was that survivors reported the gas to have first smelt of sweet apples. That is the strange thing about poisonous gases. So many of them smell quite good. Lewisite, a poison gas from the First World War, smelt of geraniums, phosgene of freshly mown hay, arsine gas of garlic, hydrogen cyanide of almonds while the nerve gas soman smells of Vicks vapour rub. The worst is probably hydrogen sulphide, which pongs of rotten eggs. And there are many other perilous vapours that have no odour at all.

To this day Halabja remains the world’s largest gas attack on a civilian population ever recorded. Unpublicised is the fact that Bloody Friday was preceded by at least 21 other gas assaults. None of those made it to the news. Some blame Iran for its involvement as Iraq was not known to possess hydrogen cyanide. Iran certainly was. Whoever was to blame, whatever agent was used, Bloody Friday was classed as genocidal and changed the face of the world.

The third option for Kurdish independence may well be the most likely. One day we wake up and the Kurds have just done it. They declare unilateral independence and wait for the bang. How would Baghdad react? Not well, I suspect. So, who can the Kurds turn to for help?

Strangely, that might be Turkey, the land which for so long has opposed an independent Kurdistan, certainly within its own borders. Yet WikiLeaks has already published documents to show that Iraqi Kurdistan has tried to sell some of its oilfields to Turkey for a massive $US5 billion. This is as part of a loan paid to the KRG by the Turks.

Unsurprisingly, right now the oil companies are worried. Exxon Mobil has withdrawn three of its six exploration blocks in the Kurdistan region. The public image states this is because of decreasing production and has nothing to do with politics. Really? There is so much talk now about the region heading towards civil war. A Kurdish journalist has been assassinated, honour killings continue apace, there have been death threats against a female Kurdish parliamentarian, there was a bombing of the Iranian Kurdish party offices that killed seven people and several terrorist attacks have recently been foiled in Suli province. Add to these the demonstrations by civil servants thanks to unpaid or reduced salaries as well as an increasing number of refugees and watch that space for Kurdistan.

For the moment, it is Islamic State this and Islamic State that. But as one declines others come to a head. Civil War in Kurdistan? It is certainly a possibility. Once again, it would not be a good day.

Flag of Kurdistan

Joy upon joy. Sulaimaniyah also has mountains.

Slemani on a nearby mountain, displayed for all to see (Baxtiyar Goran on Twitter).