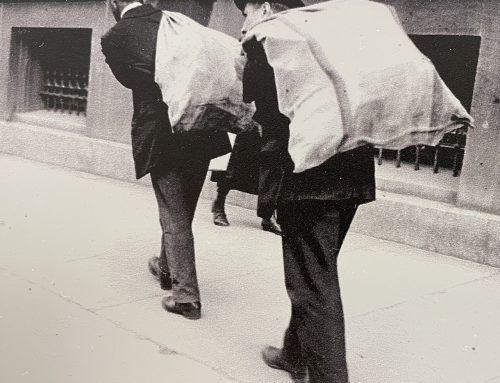

Humanitarians need balls

Humanitarians need these

Humanitarians need these

Hitzkirch, Switzerland

I am unsure what made me glance to the left as I leaned hard to open the cheap mahogany door into the cold night air beyond. Maybe habit, maybe instinct, perhaps too many moments spent in dubious locations, but look left I did. And there he stood.

Five foot eight, or thereabouts, clearly fit, manifestly strong and dressed from head to toe in white. White trainers, trousers, belt and shirt, and over everything, white hoodie. The occupant, because in my world folk do not wear hoodies, they occupy them, had the hood drawn well down as shelter from the freezing fog. Through a tiny crack somewhere near his left cheek I could see the black face draw hard on the roll-your-own cigarette. The guy somehow made smoking attractive.

“You make that look so-o-o-o good,” I commented. Imagine me, the vehement antismoker saying that?

The guy flicked his head upwards, the hoodie following the same path, and immediately I could see the smile.

“Want one?” he asked. The French accent made his English difficult to understand, although the casual wave of the cigarette in my direction made the meaning clear.

“No thanks,” I replied. I’ve enough trying to kill me as it is, without adding to the list.”

He laughed, then I laughed, and before either of us thought further we had burst into peals of mirth. We were clearly hysterical as I knew for a fact that the guy pulling on the fag, right there before me, should have been a long time dead. But he was not. He was massively alive, good bubbling company, and somehow was still working as a surgeon in one of the planet’s most troublesome war zones. Death threats were routine, murder a survival tool. His land, even on a good day, could make Middle Eastern conflict look like a military exercise. Genocide was not a thought process where he came from, it was seen by some to be almost normal. Personally, I have not the least idea what goes through their heads.

Enter the humanitarian worker and he, or increasingly she, tries hard to tread that middle ground, the clear water between two opposing factions. The principle is easy. If both sides are happy to see you that is fine. But in so many conflicts, there is one faction with an upper hand and another on the run. Losers tend to have worse health, less food, more injuries, fewer facilities and homes that have been destroyed. They are the natural target for the humanitarian. Meanwhile the winners, not without misery and deprivations themselves, are trying to make the losers even worse. How easy it is for a well-meaning humanitarian’s actions to be misinterpreted by the fighters as support for the losing side, not aid for the needy. No wonder insurers look dubiously at humanitarians.

Somehow the organisation had found 30 of us, from places in the world you may never have heard. The common factor, as best I could tell, was that all present spent their lives in harm’s way, received little or no payment, and zero public recognition for what they did. The reward? Heaven had better exist because if it does not, I have some serious debating ahead with St Peter. Few can explain why they do these things, it is futile to ask, but the fact they do is pretty, seriously incredible.

One might imagine, once the humanitarian has crawled from his hole in the ground, his only protection from shellfire in the war-shattered village of, say, Outer Popapepakettle - please say that three times fast - and made his way to Switzerland and into the arms of the organisation’s warm embrace, that luxury would await. Sorry, that is not the way it is done. It may be cost, it may be simplicity, or indeed it may be security, but these meetings seem always to take place in remote farm buildings, unpronounceable industrial estates, or touchie-feelie centres for reformed drug addicts somewhere in the middle of a field. And a bar? Not a hope. A café? If you are lucky. Even should there be one, battle must be done with what I sensed was a retired Sergeant-Major, who held on to the tiny tokens allowing access to a coffee machine as if she had been instructed to defend them with her life. Actually, on one occasion, with me calorie-deficient and a blood glucose in my boots, she nearly had to. Until I overheard the Token Queen had a black belt in karate and I might come off worse. I smiled, pretended to speak Japanese only, and enjoyed a glass of water.

Yet the purpose of our meeting was critical. You see, people keep shooting, maiming. exploding, disembowelling and generally being intolerant of fellow man. More than likely those who are injured are those who cannot fight back. In some conflicts, more than 90% of injured would not know from which end of a rifle a bullet might appear. Use all the logic and persuasion in the universe but Mankind still resorts to violence. I worry myself when I keep reflecting that war might just be man’s unhappy but natural state. A lifetime of conflict surgery has done nothing to change that view.

Weapons are worse and more remote. Death is something that happens to others, is it not? Sadly, that is not the modern way. Heavens, I can now be killed by an overweight and spotty adolescent sat in an armchair umpteen thousand miles away while he eats salt ‘n vinegar crisps. But with these weapons come injuries - big ones, nasty ones, huge ones, the unimaginable.

The organisation had summoned us to the land of the cuckoo clock to put us through our paces and to be sure we were up to speed. Frighteningly all the training was true. I mean, what do you do when 183 wounded arrive at the hospital’s front door over 15 minutes thanks to a teenager keen to try out his new exploding jacket and all you have is you, you, you and you? How do you react when you are busy resuscitating a seven-year-old girl and a soldier shoves an AK47 in your eye and tells you to treat his friend’s hangover? What do you do when a sniper decides your hospital’s roof makes a perfect spot from which to pick off the opposition? Do you truly have the courage to ask the fellow to move? And how about it if an unexploded bomblet ends up inside a patient? Yes, inside the living frame, not lying on the road outside but deep within a large and open wound on the front of the patient’s shoulder. Are you so courageous that you will take it out, defuse it and repair the wound as well?

Think I am joking? Sorry, I am not. Each of these events truly happened, and not so long ago. No wonder humanitarians need balls.

Humanitarians so often work in dangerous places and become targets themselves.