Do not talk with humming birds

Do not talk with hummingbirds. They fly away if you do.

Do not talk with hummingbirds. They fly away if you do.

Putre, Chile

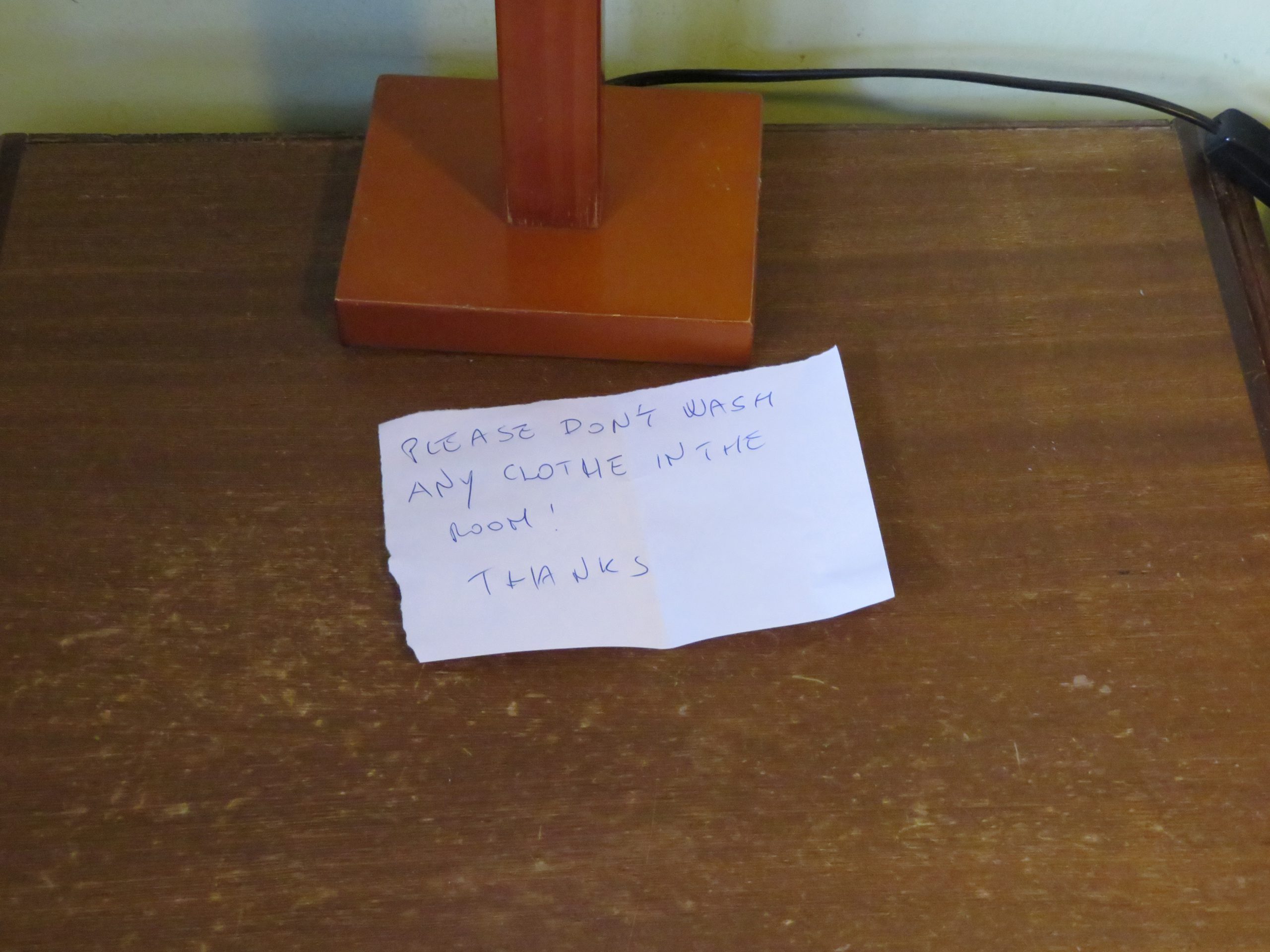

I am so terribly sorry. It is me who is to blame. Hands up, I have been caught red handed. Sorry, Miss, it was me who washed his underwear in the bathroom sink.

Clearly, in Chile’s Putre, this was simply not done. I blamed myself, of course, as I knew I should not have mentioned Fawlty Towers, that John Cleese wonder, when checking in to the hotel. Perhaps it was the lofty altitude of 3500 metres and the diplomatic portion of my brain had defunctioned. Perhaps it was simply too tempting. The hotel, splendid though it was, had an air of charming ill-discipline about it and I was subconsciously wishing to join in.

One feature of non-stop travel, and I was on a lengthy voyage without rest, are the strange places you find yourself and, as a writer, the even odder places you are obliged to craft your words. On this occasion, I was in a half-darkened room, walls as thin as tissue, and sat on a cold, white plastic chair. The chair was made colder by the -8°C temperature and whistly wind that I could both hear and feel outside. The only thing absent was a howling wolf and even that did not seem far away.

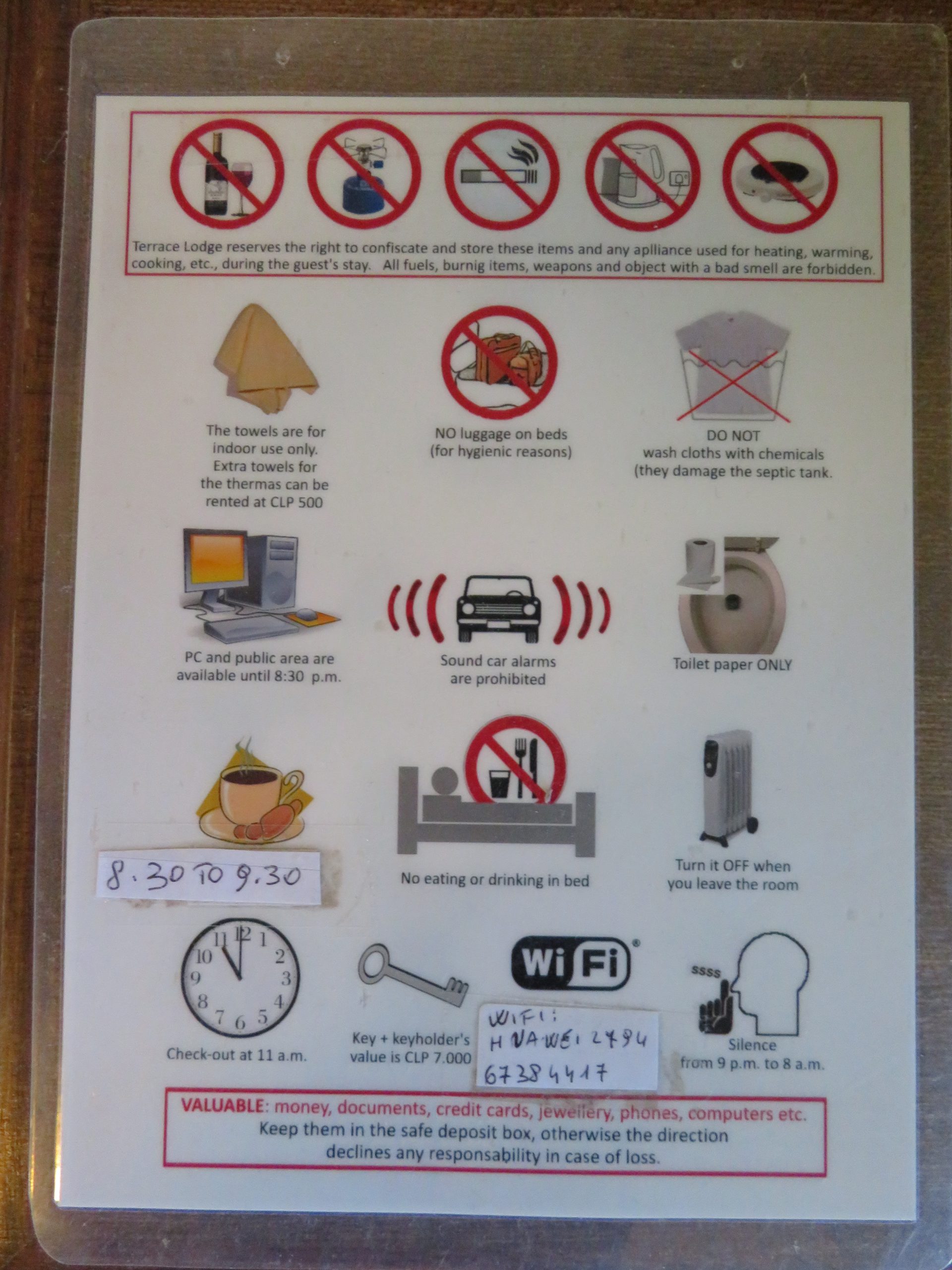

Putre is one of several gateways to the real Atacama and to all those sights you will never see elsewhere. Its choice of hotels? Fine, I suppose, but do not opt for five-star comfort and don’t even think of washing your clothes. My room was littered with as many warning notices as I can recall seeing, more so than a motorway or a London road. Do not put luggage on the beds, do not use the towels outdoors and definitely do not sound your car alarm. No problems there, I thought, as the car in which I travelled was not my own. Do not eat in bed, drink alcohol, use gas cookers, smoke, boil a kettle, or lose a key.

And yes, I had promised to be silent between nine at night and 8 a.m, which was why I was working busily at six in the morning, holding my breath in case I was heard. Fine, until my mobile alarm went off shortly before seven. I am an early-bird-writer, you see. I stopped the alarm on the second ring, having poked hard at the screen’s red button. I felt proud as my reactions had been clearly up to par. Until I heard the groaning from the room next door, the shuffling and turning in bed of a neighbour, followed by their low-tone whispers through the wall that separated us, mumbling something odd in Spanish, but sounding like, “What the Hell was that?”

Meanwhile, above my head, on the small pine-framed mirror, was a tiny paper sign, written in both English and Spanish. “In Putre there are no dangerous mosquitoes,” it declared. “Any small insect or moth you find is harmless. If you still want to kill it, please do not do it on the wall.” Fair point, I suppose. Squashed insect bodies must be Hell for decoration. Mind you, as I listened to the wind outside and had still to kick life into my cold hands, I could not see how any insect could possibly survive let alone fly.

Anyway, I dared not turn on the room gas heater as that, too, carried a warning sign. I was ordered, yes ordered not asked, to use only it from 5 p.m., and only to positions 1, 2, 3 or 4 from a total of 7. Otherwise, the sign declared, low atmospheric pressure could extinguish the heater’s flame. My fate should that happen was not explained, but I sensed a slow and miserable death from carbon monoxide. It seemed safer and simpler to freeze.

My hotel was also one of lost opportunity, as happened to me a short while later. Having awoken half of civilisation thanks to my mobile’s klaxon alarm, I gingerly opened my room door, tiptoed up a short flight of irregular stone steps and took up station in a narrow hotel passageway that was open to the elements on one side. My positioning was cunning, I thought, as I had been trying to send an email to Blighty from my room but the wifi had been worse than useless. I had tut-tutted with frustration as I had climbed the steps but then placed myself outside the locked office that I knew housed the hotel’s router. The closer I was to router the more likely I would have success.

It was cold, my vapoured breath said all, there was nowhere to sit, so I stood, with my computer balanced precariously on my left forearm. I tried with my right hand to type a message back home to those who wished to view my labours. I was already three days late with copy. My two-handed typing was bad, my one-handed efforts were horrendous. Shocking was the only valid description.

I got there eventually with more than a dozen corrections each line. Signal strength teetered at one bar, maybe two, so I clicked the on-screen arrow, the one that indicates “Send”. There was an anaemic whoosh, normally it is assertive, and off my message limped.

Hotel awake, message sent, writer frozen, it was time to take cover in my room once more, maybe try warming in bed under the wafer-thin, green-tinted quilt supplied. I was about to turn, head for the steps, this time to descend rather than climb, when I heard the sound. It was not something I had heard previously, it was definitely different and was certainly not my chilled and part-frosted computer, whose screen I had yet to close.

“Brrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr. Brrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr. Brrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrrr.” It was medium pitch, bee-like, and I could sense a nearby vibration, almost a gentle wind on my left cheek. It was as if something was stirring. Instantly I knew something was nearby, I had no idea what, but an inner sense told me to move with care. Now distracted from my computer screen, which was swaying dangerously on my forearm, I looked up slowly, and slightly to my left.

And there it was. There, perhaps ten centimetres from my face, its wings flapping on automatic, its body stationary in mid-air. The long beak of the hummingbird was but a peck distance from my left eye. For sure, a hummingbird. They have them in Chile by the hundred.

Yet with hummingbirds there is a constant feature. Whoever you are, wherever you find yourself positioned, you will want to photograph it. Believe me, that is how it is. But however skilled you may feel, it will not allow you. Even think the word “photograph”, you do not have to move, and the bird will flit away, darting from plant to plant, tree to tree, object to object, perfectly camouflaged, before it disappears. Never try to photograph a hummingbird, you will surely fail. For certain, it will defeat you and even read your thoughts.

On this occasion, my left arm was immobilised by my computer and my camera-ready mobile was in a right-hand pocket and irretrievable. So, I did what any other person would have done, sane or crazy, Chilean or foreigner, boy, girl or indifferent. I said, “Good morning, Mr Hummingbird,” with the broadest smile I could muster.

And you know what? I wager the hummingbird smiled back. Then, with a hummingbird nod, a hummingbird bow, or maybe a hummingbird curtsey, it was away, flitting from plant to plant, tree to tree, object to object before rapidly becoming invisible.

I tried to close my mouth but the thing just would not shut, staying open in astonishment at the hummingbird hover. So, I quietly closed my computer screen, at least that would shut, turned slowly on my heel with the gentlest of squeaks and headed towards the stone steps and my do-not-do-anything room. First thing to check, I thought as I descended, was to see if I had missed the sign, forbidding me to talk with hummingbirds.

Message on my table. Oh dear, I washed my clothes.

Do not do this, do not do that