Someone died today

It happened here

It happened here

Litochoro, Greece

Someone died today, in a most horrible way. Death in the mountains is always ghastly, invariably unexpected and frequently plucks a young person from a life of ambition, an existence full of future, and rips a family apart. Today has been no exception.

He was from the Balkans – I do not know his name – but he was attempting to reach the summit of Mount Olympus in Greece. In his late twenties, he was climbing with a group of friends. One in particular was right beside him. Then, for no reason, the sharp rocky surface that is such a feature of Olympus began to slide, and down he went. Tumbling, falling, sliding, and no helmet for protection. It did not take him long to die. His friend was luckier, maybe quicker, and managed to side step the rock fall. His only injury was a lacerated chin.

No one knows why the rock fall happened but the best guess is an earthquake. There have been plenty of small ones in Greece over the last few days. However, Olympus is notorious for rock fall and it is easy to stray from the recommended path, so brilliantly displayed by red and yellow markers. The sheer face, a challenge to even the strong hearted, has several narrow gullies that channel rock straight at you. All that is needed is a nervous climber above, perhaps scrabbling for a foothold, and the next thing is the entire face is flying downhill and you are in its way, or even on your way – in the wrong direction.

A death on a mountain understandably leaves a depressed air. Folk might say why it was the climber’s fault, perhaps hypothesise what he might have done wrong, but the reality is that accidents occur even to the best. Mallory, Boardman, Tasker? I bet they did not go out that day in order to end up dead. These things happen suddenly, just when your eye is turned. Ask any mountain guide or leader. You can be climbing with a good colleague, maybe a client, chatting away about this and that. Suddenly, within the blink of an eye, your lives can fall apart. It has happened to me more than once, it has happened today on Olympus, and there is often nothing but fate and misfortune to be blamed.

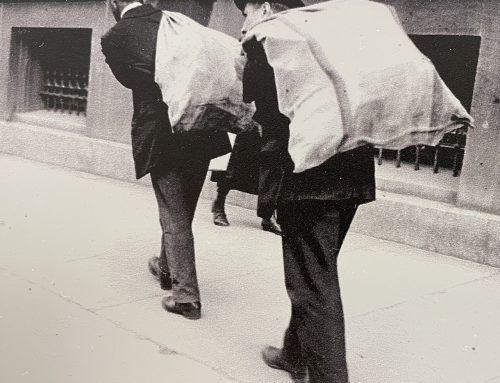

I passed the survivors as they were descending. What could one say? So much, yet so little. All I could do was hide guiltily behind their lack of English, perhaps my ignorance of their language, which prevented adequate communication. You know that feeling when you pass a homeless man on a city pavement, as he tries hard to sell a copy of The Big Issue. How many of us know we should stop but how many of us actually do so? It was the same on Mount Olympus. The doctor inside me wanted to offer the world’s biggest hug but all I did was to mumble a sound like “Yassas” (Greek for “Hi”) and I walked on past. That is on my conscience, not theirs, but I wish now I had handled it differently. Their eyes were sunken, their pace suppressed and they barely spoke to one other, let alone me. I should have done better, I should have shown support, but I failed.

Mountain rescue, when I met them later in the day, were more laid back. They had retrieved bodies from Olympus on many previous occasions. There was nothing new to them about this one, other than the tragedy had occurred on what is seen by most as the safest of the mountain’s routes. I am not sure I would agree with that reputation.

“Did you take him down by helicopter?” I asked.

Mountain rescue looked puzzled. “Helicopter? Why?”

“I thought it would be…”

“No.” they interrupted, as if I had asked a daft question. “Why waste helicopter hours on the dead? We use them for the living. He was placed in a body bag and has gone down the mountain by mule.”

There is something tragic about zipping a dead young climber into a body bag, strapping it to a mule and making his friends and family walk down later. How does a friend or relative recover from that? I doubt they ever can. How I wanted to speak their language today, just to help those poor folk handle the emotion, but I failed, I failed, I failed.

I have spent excessive years in the mountains, in many different parts of the world. Sadly, death is something I have encountered on several occasions, even in outwardly innocent places like the Brecon Beacons, in the United Kingdom’s South Wales. Each time there is the same response. The attempt by others to explain why someone perished and to blame the dead for their own demise. The fact it might have been unavoidable is never considered. There must always be an explanation. The first hand survivors, those who were actually at the scene of death, are wrecked and may take many years to recover. It is the second hand survivors, those who were further away, albeit still in the area but not directly exposed to danger themselves, who appear to have the strongest views. Is it that they wish to feel part of the event?

It is almost a form of voyeurism, where fellow climbers sit around refuge tables looking earnest, holding hushed conversations, and making out they are knowledgeable. The fact is they may not be so clever. They were simply in the right place at the right time, not the wrong place at the wrong time. They had luck on their side.

Yet life moves on as well. As I passed the Balkan group heading down the mountain, as I watched the precariously placed dressing on the face of the climber who survived, as I held myself back from trying to reapply it and make a better job, I could hear the giggling and chanting from a school group that had spent the night in the same refuge as the survivors. The school group had not summited the peak. To these young people, the waters had already closed over, the dead had been discarded and life was already full of joy, banter and friendship.

That, I suppose, is life. We are here for such a short time – this is not a rehearsal – and our very lives can be plucked from us without warning. Somehow, when it happens to someone else, we feel that we are the worthy exception. Perhaps some unseen hand has spared us because we are special and they are not? No way. Do not fancy yourself. We will each disappear one day; remember that every morning when your eyes first open. See enough death and that fact will not escape you. Each day is most definitely a bonus and we, you, I will be replaced by those that follow. Ask the Balkan climbers on Olympus. The climber dies, he is swept up, put in a bag, goes off on a mule, and yet life still goes on. It is as though the tragedy never happened. And yet it did, and whole existences have been destroyed as a result.

It was Edward Whymper who said it, that doyen of mountaineering, the first man up the Matterhorn, and a household name even to those who come out in a rash when they see anything higher than one hundred feet. I keep a copy of his statement in the top pocket of my rucksack, alongside the champagne cork from a celebration held on the Lake District’s Helvellyn some years back.

Oh, how wise Whymper was when he said:

“Climb if you will but remember that courage and strength are nought without prudence and that a momentary negligence may destroy the happiness of a lifetime. Do nothing in haste; look well to each step; and from the beginning think what may be the end.”

I echo that.